Issues

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

How can I keep track of bugs and problems?

How can I communicate them to users?

Objectives

Learn what issues are and how to use them.

Create an issue on GitHub.

As a piece of software is used, then bugs will inevitably come to light - nothing is perfect! If you work on your code with collaborators, or have non-developer users, it can be helpful to have a single shared record of all the problems people have found with the code - not only to keep track of them for you to work on later, but to avoid the annoyance of people emailing you to report a bug that you already know about!

Issues

GitHub provides a framework (as does GitLab!) for managing bug reports, feature requests, and lists of future work - Issues.

We’ll run through an example of how to create and use them. As part of our setup we created a repository from the climate-analysis template. It’s a mock repository for a code that analyses climate data files.

Setup

If you didn’t make a copy of it earlier, go to this link and create a new repository on your account called

climate-analysis. If you’ve already got aclimate-analysisrepository from completing earlier training with us, then you can use that one!

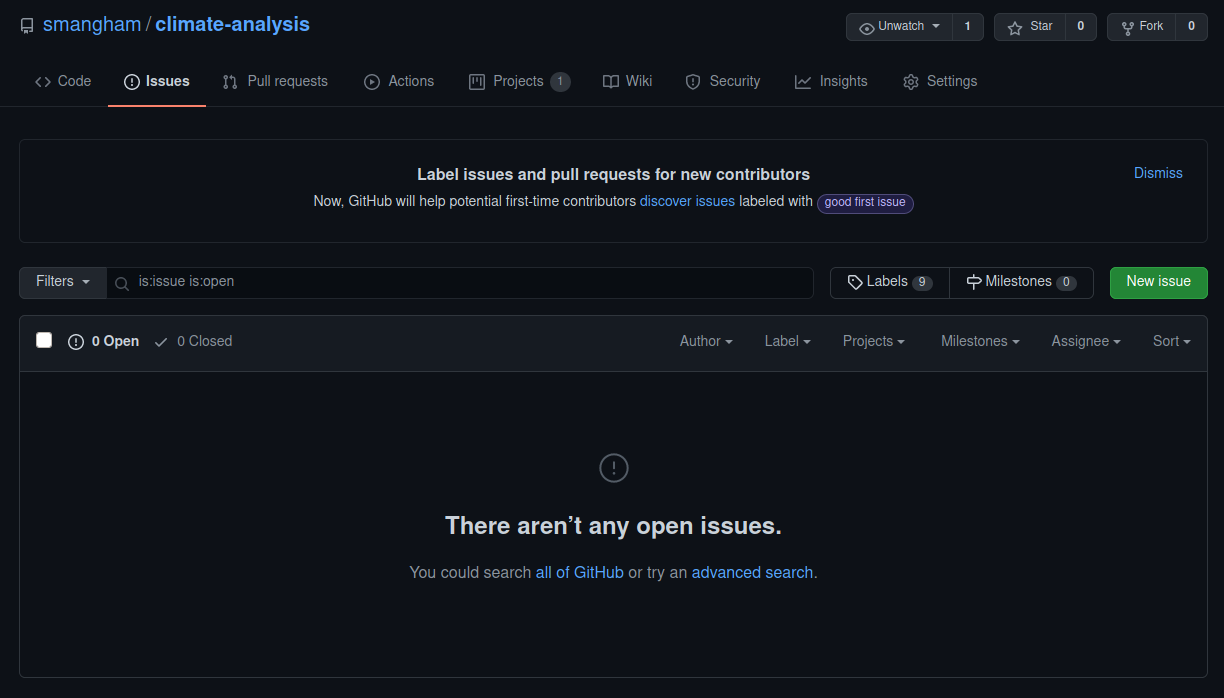

Go back to the home page for your climate-analysis repository, and click on the Issues tab. You should see a page listing the open issues on your repository, currently none.

If we look at the climate_analysis.py file in our repository, we can see that it’s got a comment describing work that needs to be done (a.k.a. a “To Do note”):

# TODO(smangham): Add call to process rainfall

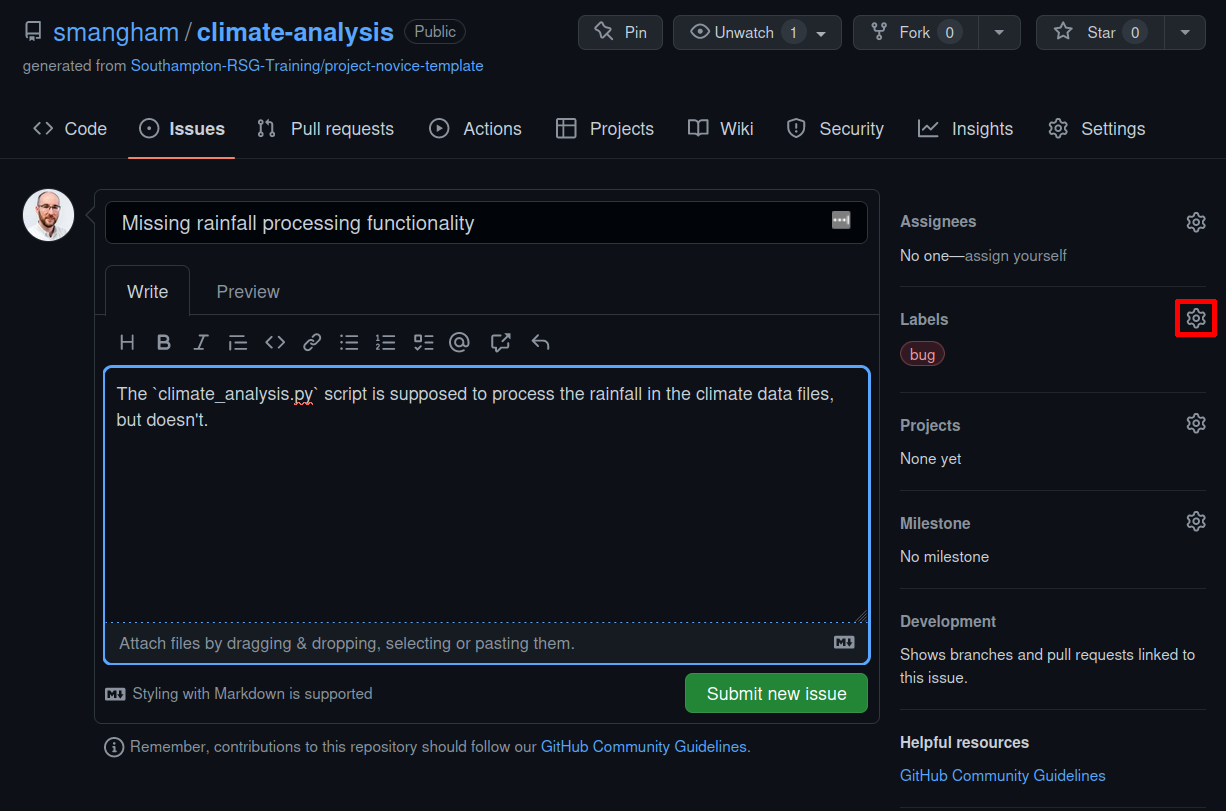

This is an easy way to record information about your code, but it’s not very accessible - if the code is in multiple files, you have to read all of them to know what the state of it is. It’s just not a very practical solution and makes it harder for new developers and users to understand your code. Instead, we’re going to create a new issue, raising the problem that the rainfall processing functionality isn’t yet working.

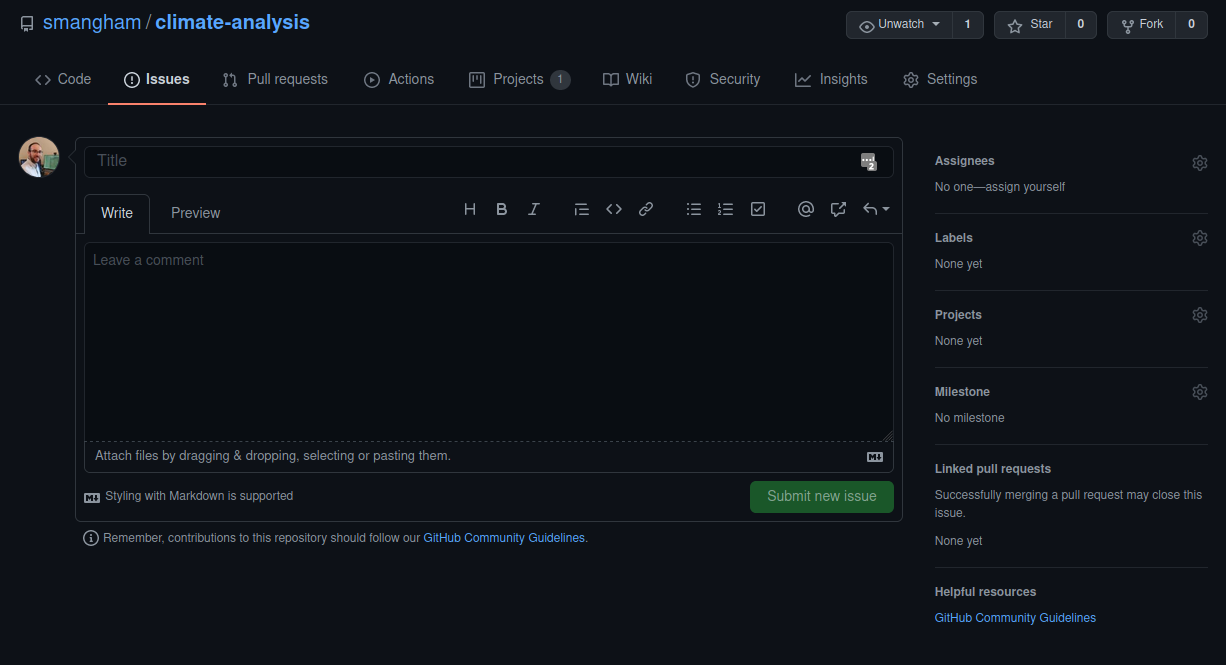

When you create an issue, you can add some extra details to it. Issues can be assigned to a specific developer - this can be a helpful way to know who, if anyone, is currently working to fix an issue (or a way to assign responsibility to someone to deal with it!). We’ll dodge responsibility for now.

You can also label an issue to describe what type of thing it is. We’re going to assign this issue the label Bug, by clicking on the cogwheel by the Labels section on the right hand column, then submit the issue.

The labels available for issues can be customised, and given a colour, allowing you to see at a glance from the Issues page the state of your code. The default labels include:

- Bug

- Documentation

- Enhancement

- Help Wanted

- Question

The Enhancement label can be used to create issues that request new features, or if they’re created by a developer, indicate planned new features. The Bug label makes the code much more usable, by allowing users to find out if anyone has had the same problem before, and how to fix (or work around) it on their end. Enabling users to solve their own problems can save you a lot of time and stress!

The Enhancement label is a great way to communicate your future priorities to your collaborators, and also your future self - it’s far too easy to leave a software project for a few months to write a paper, then come back and have forgotten the improvements you were going to make. If you have other users for your code, they can use the label to request new features, or changes to the way the code operates. It’s generally worth paying attention to these suggestions, especially if you spend more time developing than running the code. It can be very easy to end up with quirky behaviour because of off-the-cuff choices during development. Extra pairs of eyes can point out ways the code can be made more accessible, and the easier a code is to use, then the more widely it will be adopted and the greater its impact will be.

Bug or Enhancement

Is the issue we just added really a bug? In this case we could call it an Enhancement - it depends on whether we think this is missing functionality that should be there (a bug), or new functionality we want to add to an existing code. If it doesn’t suit either, we could just leave it unlabelled - labels just exist to make things clearer, after all.

Having open, publicly-visible lists of the the limitations and problems with your code is incredibly helpful. Even if some issues end up languishing unfixed for years, letting users know about them can save them a huge amount of work attempting to fix what turns out to be an unfixable problem from their end. It can also help you see at a glance what state your code is in, making it easier to prioritise future work!

It also helps give users more confidence that your code is actively used and developed - it’s much better to see an open discussion about the use of a tool or library than silence.

You Are A User

This section focuses a lot on how issues can help communicate the current state of the code to users. As a developer, and possibly also the only user of the code too, you might be tempted to not bother with recording issues and features as you don’t need to communicate the information to anyone else.

Unfortunately, human memory isn’t infallible! After spending six months writing your thesis, or a year working on a different sub-topic, it’s inevitable you’ll forget some of the plans you had and problems you faced. Not documenting these things can lead to you having to re-learn things you already put the effort into discovering before.

Exercise: Should Old Issues Be Forgot

Information decays very quickly. Try and remember all of the problems you had with a code you worked on a few years ago, for example your undergraduate final project. Were there any combinations of input settings that it couldn’t cope with, for example?

Solution

To give some examples from real PhD projects:

- A simulation code designed to run on a supercomputer could be restarted if it stopped mid-way through a simulation, but not all the outputs would be valid after restarting.

- An astrophysics simulation code would take multiple times times longer to run and give less-accurate answers if the density of gas was raised too high.

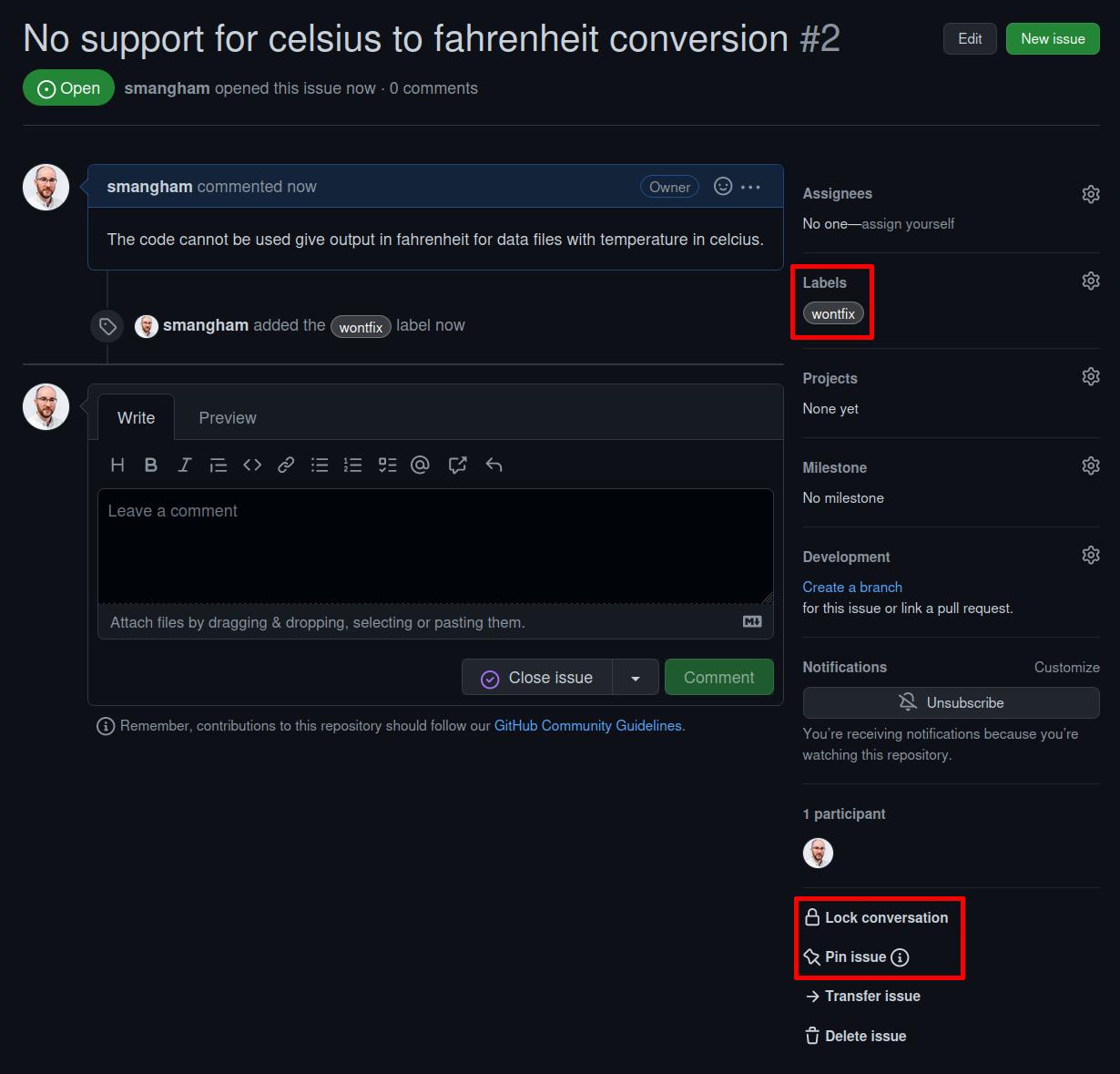

Wontfix

One interesting label is Wontfix, which indicates that an issue simply won’t be worked on for whatever reason - maybe the bug it reports is outside of the use case of the software, or the feature it requests simply isn’t a priority.

The Lock issue and Pin issue buttons allow you to block future comments on an issue, and pin it to the top of the issues page. This can make it clear you’ve thought about an issue and dismissed it!

Issue Templates

Whilst many academic software projects have only user-developers, for others many of the users will not have any experience working on the code, and in some cases not even have any software development experience at all.

Getting them to raise issues in a way that’s clear, helpful and provides enough information for you to act on (without going back and forth to extract it) can be hard. Fortunately, GitHub provides Issue templates. These allow you to set a template that anyone raising an issue is prompted to fill in. GitHub provides a range of default templates, but you can also write your own.

If you have a project with a large number of user-submitted issues, consider setting up issue templates. For more information on them, check out the GitHub documentation here.

Mentions

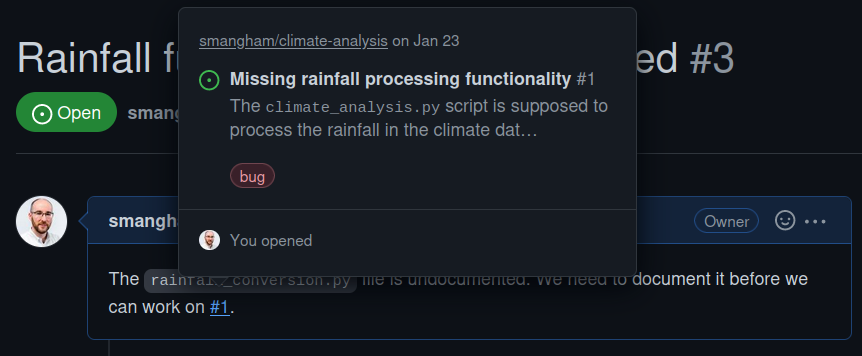

As lots of bugs will have similar roots, GitHub lets you reference one issue from another. Whilst writing the description of an issue, or commenting on one, if you type # you should see a list of the issues and pull requests on the repository. They are coloured green if they’re open, or white if they’re closed. Continue typing the issue number, and the list will narrow, then you can hit Return to select the entry and link the two. You can also navigate the list with the ↑ and ↓ arrow keys.

If you realise that several of your bugs have common roots, or that one Enhancement can’t be implemented before you’ve finished another, you can use the mention system to indicate which. This is a simple way to add much more information to your issues.

You can also use the mention system to link GitHub accounts. Instead of #, typing @ will bring up a list of accounts linked to the repository. Users will receive notifications when somebody else references them- you can use this to notify people when you want to check a detail with them, or let them know something has been fixed (much easier than writing out all the same information again in an email!).

Exercise: Linking Issues

We’ve documented that we’ve not implemented any rainfall processing in

climate_analysis.py, but the rainfall code we’d want to use is completely undocumented. We need to fix that first!Create a new issue, labelled Documentation, that mentions your previous issue and links to your GitHub account to reference that you’ll be fixing this issue as it’s a pre-requisite for the first one.

Then, check out the first issue you raised and see if anything has happened.

Solution

You should get a pop-up box looking like this when you enter the # key:

Once you’ve selected the existing issue, and created your new one, you’ll get a link to the previous one:

Commits

Mentions also work in commit messages! If you reference issue numbers in your commits (e.g. git commit -m "Fixes issue #65") then GitHub can automatically close issues, and will link the commit to the issue. This makes it easy for you to keep track of the changes to the code that were made in order to fix any given issue, should a similar bug crop up again in future.

Key Points

Issues are a way of recording bugs or feature requests.

Issues can be categorised by type.

Issues can reference other issues, and be referenced by commits.