2.1 Collaborative Workflow: Branches and Merging Strategies

Last updated on 2025-09-25 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What’s the relationship between development infrastructure and process?

- How access to GitHub repositories without needing a password?

- What is a feature branch, and why are they used?

- Describe the benefits and risks of using feature branches

- What are the options for merging branch commits into a baseline branch?

- What are the risks with merging code from feature branches?

Objectives

- Describe how workflow relates to process

- Set up SSH passwordless access to GitHub

- Describe the purpose of branches in a repository

- Define the elements of a feature-branch workflow

- Describe four major strategies for merging branches

- Create and use a branch

How are a Development Process and Version Control Related?

In a software development project the infrastructure - particularly the version control system - should be configured and used in way that reflects and support the team’s chosen development process. This alignment ensures that the tools in place reinforce the way the team works, rather than creating friction or bottlenecks. With a team following an agile, feature-driven workflow, the version control system should explicitly support that workflow.

Ultimately, as development processes evolve, the infrastructure should evolve with them. A version control system that reflects the development process helps to reduce coding errors, increases communications between members, streamline the collaborative process, and improves the overall efficiency and quality of the software being produced.

In the next couple of episodes, we’ll look at how to use well-established practices for using version control, using Git and GitHub as an example, to illustrate how it can support software developed using an agile approach.

(Optional) Solo Exercise: Set up SSH Keypair for use with GitHub

5 mins.

If you haven’t already, set up SSH keypair passwordless access following the SSH Key Setup instructions.

Introduction to Feature Branches

You might be used to committing code directly, but not sure what

branches really are or why they matter? When you start a new Git

repository and begin committing, all changes go into a branch — by

default, this is usually called main (or

master in older repositories). The name “main” is just a

convention — a Git repository’s default branch can technically be named

anything.

So why not just always use the main branch? While it is possible to

always commit to main, it is not ideal when you’re

collaborating with others, or when you are working on new features or

want to experiment with your code and you want to keep main clean and

stable for your users and collaborators.

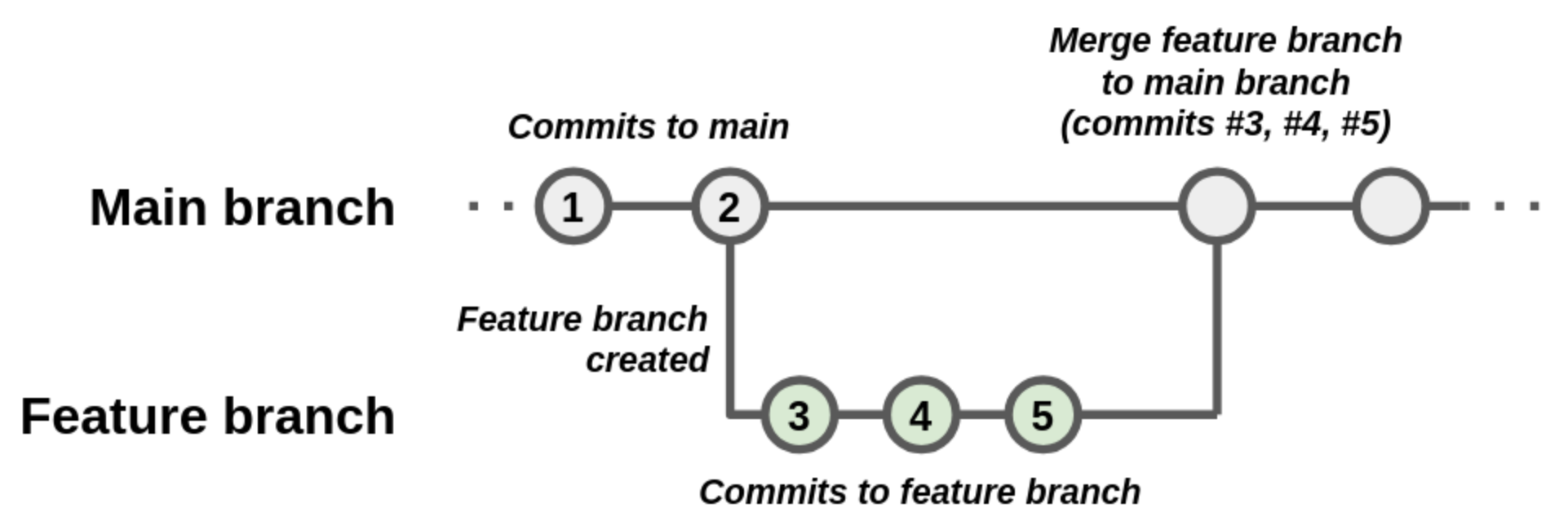

Creating and working on a separate branch, often called a “feature”

branch, allows developers to “branch off” development from a particular

commit in the repository, enabling them to make changes (as new commits)

to a branch without disrupting the main branch. When this

separate development has been tested and is judged to be ready, the

commits on this branch are then merged into the main

branch.

You should consider starting a new branch whenever you are working on a distinct feature or fixing a specific bug.

Group Exercise: Pros and Cons of Developing Code on Feature Branches

5 mins.

As a group, discuss list some advantages and disadvantages of developing code on feature branches as part of a team. Don’t consider aspects related to merging - this will be covered in a future exercise!

Advantages:

- It enables the main branch to remain stable while you and the team explore and test the new code on a feature branch

- It enables you to keep the untested and not-yet-functional feature branch code under version control and backed up

- You and other team members may work on several features at the same time independently from one another

- If you decide that the feature is not working or is no longer needed - you can easily and safely discard that branch without affecting the rest of the code

Disadvantages:

- Requires that the team understand this approach and how to use it in an agreed and consistent manner

- May become complicated if you need to use features available on another branch in your own branch

- Similarly, if

maincontains many changes not in feature branches, it may diverge considerably from these feature branches

Branch Merging Strategies

When you are ready to bring the changes from your feature branch back into the main branch, Git offers you to do a merge - a process that unifies work done in 2 separate branches. Git will take two (or more - you can merge more branches at the same time) commit pointers and attempt to find a common base commit between them. Git has several different methods of finding the base commit - these methods are called “merge strategies”. Once Git finds the common base commit it will create a new “merge commit” that combines the changes of the specified merge commits. Technically, a merge commit is a regular commit which just happens to have two parent commits.

Each merge strategy is suited for a different scenario. The choice of strategy depends on the complexity of changes and the desired outcome. Let’s have a look at the most commonly used merge strategies.

Fast Forward Merge

A fast-forward merge occurs when the main branch has not diverged from the feature branch, meaning there are no new commits on the main branch since the feature branch was created.

A - B - C [main]

\

D - E [feature]In this case, Git simply moves the main branch pointer to the latest commit in the feature branch. This strategy is simple and keeps the commit history linear - i.e. the history is one straight line.

After a fast forward merge:

A - B - C - D - E [main][feature]Fast forward merge strategy is best used when you have a short-lived feature branch that needs to be merged back into the main branch, and no other changes have been made to the main branch in the meantime.

3-Way Merge with Merge Commit

A fast-forward merge is not possible if the main and the feature branches have diverged.

A - B - C - F [main]

\

D - E [feature]If you try to merge your feature branch changes into the main branch and other changes have been made to main - regardless of whether these changes create a conflict or not - Git will try to do a 3-way merge and generate a merge commit.

A merge commit is a dedicated special commit that records the combined changes from both branches and has two parent commits, preserving the history of both lines of development. The name “3-way merge” comes from the fact that Git uses three commits to generate the merge commit - the two branch tips and their common ancestor to reconstruct the changes that are to be merged.

A - B - C - F - "MergeCommitG" [main]

\ /

D - E [feature]In addition, if the two branches you are trying to merge both changed the same part of the same file, Git will not be able to figure out which version to use and merge automatically. When such a situation occurs, it stops right before the merge commit so that you can resolve the conflicts manually before continuing.

Rebase & Merge

In Git, there is another way to integrate changes from one branch into another: the rebase.

Let’s go back to an earlier example from the 3-way merge, where main and feature branches have diverged with subsequent commits made on each (so fast-forward merging strategy is not an option).

A - B - C - F [main]

\

D - E [feature]When you rebase the feature branch with the main branch, Git replays each commit from the feature branch on top of all the commits from the main branch in order. This results in a cleaner, linear history that looks as if the feature branch was started from the latest commit on main.

So, all the changes introduced on feature branch (commits D and E) are reapplied on top of commit F - becoming D’ and E’. Note that D’ and E’ are rebased commits, which are actually new commits with different SHAs but the same modifications as commits D and E.

A - B - C - F - D' - E' [main]

\

D - E [feature]At this point, you can go back to the main branch and do a fast-forward merge with feature branch.

Rebase is ideal for feature branches that have fallen behind the main development line and need updating. It is particularly useful before merging long-running feature branches to ensure they apply cleanly on top of the main branch. Rebasing maintains a linear history and avoids merge commits (like fast forwarding), making it look as if changes were made sequentially and as if you created your feature branch from a different point in the repository’s history. A disadvantage is that it rewrites commit history, which can be problematic for shared branches as it requires force pushing.

The Golden Rule of Rebasing

Note that you can also do rebasing with branches on the command line. But a word of warning: when doing this, be sure you know what will happen.

Rebasing in this way rewrites the repository’s history, and therefore, with rebasing, there is a GOLDEN RULE which states that you should only rebase with a local branch, never a public (shared) branch you suspect is being used by others. When rebasing, you’re re-writing the history of commits, so if someone else has the repository on their own machine and has worked on a particular branch, if you rebase on that branch, the history will have changed, and they will run into difficulties when pushing their changes due to the rewritten history. It can get quite messy, so if in doubt, do a standard merge!

Squash & Merge

Squash and merge squashes all the commits from a feature branch into a single commit before merging into the main branch. This strategy simplifies the commit history, making it easier to follow. This strategy is ideal for merging feature branches with numerous small commits, resulting in a cleaner main branch history.

A - B - C - F - "SquashCommitG" [main]

\

D - E [feature]Note that unlike the 3-way merge, SquashCommitG only has

one parent, F, so does not preserve the link to the commits

on the feature branch upon which SquashCommitG is based.

This has caused some to consider squash commits harmful, since that part

of the commit history is lost. For this reason, squash commits are handy

when you want to clean up a commit history from a short-lived feature

branch prior to merging to main, but problematic with

longer lived branches or when maintaining commit history is

important.

FIXME: verify squash commit has only 1 parent when using a squash-merged PR

Summary

Here is a little comparison of the three merge strategies we have covered so far.

| Fast Forward | Rebasing | 3-Way Merge | Squash Merge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Maintains linear history | Maintains linear history | Non-linear history (commit with 2 parents) | Linear history (commit with 1 parent) |

| Effect on main | No new commits on main | New commits on main | New commits on main | One new commit on main |

| Merge commit? | Avoids merge commits | Avoids merge commits | Uses merge commits | Avoids merge commits |

| When it works | Only works if there are no new commits on the main branch | Works for diverging branches | Works for diverging branches | Works for diverging branches |

| Rewrites history? | Does not rewrite commit history | Rewrites commit history | Does not rewrite commit history | Does not rewrite commit history |

FIXME: callout

FIXME: challenge - which approach suits your use of version control in most cases? and scenarios for when to and when not to squash merge: twenty people giving many commits to a single feature branch (i.e. want to keep history), simple changes that need to revert (i.e. changing colours back and forth, or testing)

Group Exercise: Merging - What are the Risks?

5 mins.

In general, as a group identify the risks are with merging code from branches in a team environment.

Here are several non-exhaustive reasons:

- A merge may introduce errors that cause the software to break or fundamentally change its behaviour in ways that are unintended but not immediately obvious

- There may be a variability in the quality or style of written code that leads to inconsistency across the codebase

- Team members may not be aware of important changes being made in other branches that will affect their work

- Work may be unknowingly duplicated, or introduce conflicting solutions, e.g. where there are logical overlaps between coding tasks in different branches

- The reasoning behind changes may be unclear

- Long-lived branches may become too divergent from the

mainbranch, complicating the process of merging changes from such branches - Similarly, implementing and then merging multiple feature branches simultaneously becomes exponentially more difficult

The benefits of using feature branches are generally considered to vastly outweight such drawbacks, and as we’ll see in the next episode, there are features we can introduce to using feature branches that aim to mitigate these drawbacks by introducing additional steps that increase communication among team members.

- Infrastructure and tooling used by a team must support agreed healthy development processes and practices but not unnecessarily dictate them

- Once you’ve set up personal SSH access to GitHub from a machine, you do no need to use passwords

- Separate features or bug fixes should be developed on separate repository branches and merged to the main branch when ready

- Developing code on feature branches enables the main branch to remain working and clear of unfinished features or bug fixes, and prevents confusion across separate development activities

- A fast-forward merge simply adds commits to the end of a destination branch

- A 3-way merge with merge commit creates a new commit on the destination branch comprised of the commits on the feature branch

- A rebase and merge rewrites the history