Finding Things

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 15 minQuestions

How can I find files?

How can I find things in files?

Objectives

Use

grepto select lines from text files that match simple patterns.Use

findto find files and directories whose names match simple patterns.Use the output of one command as the command-line argument(s) to another command.

Explain what is meant by ‘text’ and ‘binary’ files, and why many common tools don’t handle the latter well.

Finding files that contain text

You can guess someone’s computer literacy by how they talk about search: most people use “Google” as a verb, while Bash programmers use “grep”. The word is a contraction of “global/regular expression/print”, a common sequence of operations in early Unix text editors. It is also the name of a very useful command-line program.

grep finds and prints lines in files that match a pattern.

For our examples,

we will use a file that contains three haikus taken from a

1998 competition in Salon magazine. For this set of examples

we’re going to be working in the writing subdirectory:

$ cd ~/shell-novice/shell/test_directory/writing

$ ls

data haiku.txt old thesis tools

Let’s have a look at the haiku.txt file:

$ cat haiku.txt

The Tao that is seen

Is not the true Tao, until

You bring fresh toner.

With searching comes loss

and the presence of absence:

"My Thesis" not found.

Yesterday it worked

Today it is not working

Software is like that.

Forever, or Five Years

We haven’t linked to the original haikus because they don’t appear to be on Salon’s site any longer. As Jeff Rothenberg said, “Digital information lasts forever — or five years, whichever comes first.”

Let’s find lines that contain the word “not”:

$ grep not haiku.txt

Is not the true Tao, until

"My Thesis" not found

Today it is not working

Here, not is the pattern we’re searching for.

It’s pretty simple:

every alphanumeric character matches against itself.

After the pattern comes the name or names of the files we’re searching in.

The output is the three lines in the file that contain the letters “not”.

Let’s try a different pattern: “day”.

$ grep day haiku.txt

Yesterday it worked

Today it is not working

This time,

two lines that include the letters “day” are outputted.

However, these letters are contained within larger words.

To restrict matches to lines containing the word “day” on its own,

we can give grep with the -w flag.

This will limit matches to word boundaries.

$ grep -w day haiku.txt

In this case, there aren’t any, so grep’s output is empty. Sometimes we don’t

want to search for a single word, but a phrase. This is also easy to do with

grep by putting the phrase in quotes.

$ grep -w "is not" haiku.txt

Today it is not working

We’ve now seen that you don’t have to have quotes around single words, but it is useful to use quotes when searching for multiple words. It also helps to make it easier to distinguish between the search term or phrase and the file being searched. We will use quotes in the remaining examples.

Another useful option is -n, which numbers the lines that match:

$ grep -n "it" haiku.txt

5:With searching comes loss

9:Yesterday it worked

10:Today it is not working

Here, we can see that lines 5, 9, and 10 contain the letters “it”.

We can combine options (i.e. flags) as we do with other Bash commands.

For example, let’s find the lines that contain the word “the”. We can combine

the option -w to find the lines that contain the word “the” and -n to number the lines that match:

$ grep -n -w "the" haiku.txt

2:Is not the true Tao, until

6:and the presence of absence:

Now we want to use the option -i to make our search case-insensitive:

$ grep -n -w -i "the" haiku.txt

1:The Tao that is seen

2:Is not the true Tao, until

6:and the presence of absence:

Now, we want to use the option -v to invert our search, i.e., we want to output

the lines that do not contain the word “the”.

$ grep -n -w -v "the" haiku.txt

1:The Tao that is seen

3:You bring fresh toner.

4:

5:With searching comes loss

7:"My Thesis" not found.

8:

9:Yesterday it worked

10:Today it is not working

11:Software is like that.

Another powerful feature is that grep can search multiple files. For example we can find files that

contain the complete word “saw” in all files within the data directory:

$ grep -w saw data/*

data/two.txt:handsome! And his sisters are charming women. I never in my life saw

data/two.txt:heard much; but he saw only the father. The ladies were somewhat more

data/two.txt:heard much; but he saw only the father. The ladies were somewhat more

Note that since grep is reporting on searches from multiple files, it prefixes each found line

with the file in which the match was found.

Or, we can find where “format” occurs in all files including those in every subdirectory. We use the -R

argument to specify that we want to search recursively into every subdirectory:

$ grep -R format *

data/two.txt:little information, and uncertain temper. When she was discontented,

tools/format:This is the format of the file

This is where grep becomes really useful. If we had thousands of research data files we needed

to quickly search for a particular word or data point, grep is invaluable.

Grep and Regular Expressions

grep’s real power doesn’t come from its options, though; it comes from the fact that search patterns can also include wildcards. The technical name for these is regular expressions, which is what the “re” in “grep” stands for. Unlike standard wildcards (*and?), regular expressions provide a more advanced and flexible way to express complex patterns for text searches. If you want to do complex searches, please look at the lesson on our website.To give you a glimpse of

grepwith regular expressions, consider the following example:$ grep -E '^.o' haiku.txtYou bring fresh toner. Today it is not working Software is like that.In this example, the

-Eflag indicates the use of regular expressions. We put the pattern'^.o'in quotes to prevent the shell from trying to interpret it. If the pattern contained a*, for example, the shell would try to expand it before runninggrep. Now, breaking down the pattern:

- The

^(caret) anchors the match to the start of the line, much like the simple wildcards.- The

.(dot) matches any single character, similar to the?wildcard in the shell.- The

omatches the literal character ‘o’.

Finding Files Themselves

While grep finds lines in files,

the find command finds files themselves.

Again,

it has a lot of options;

to show how the simplest ones work, we’ll use the directory tree shown below.

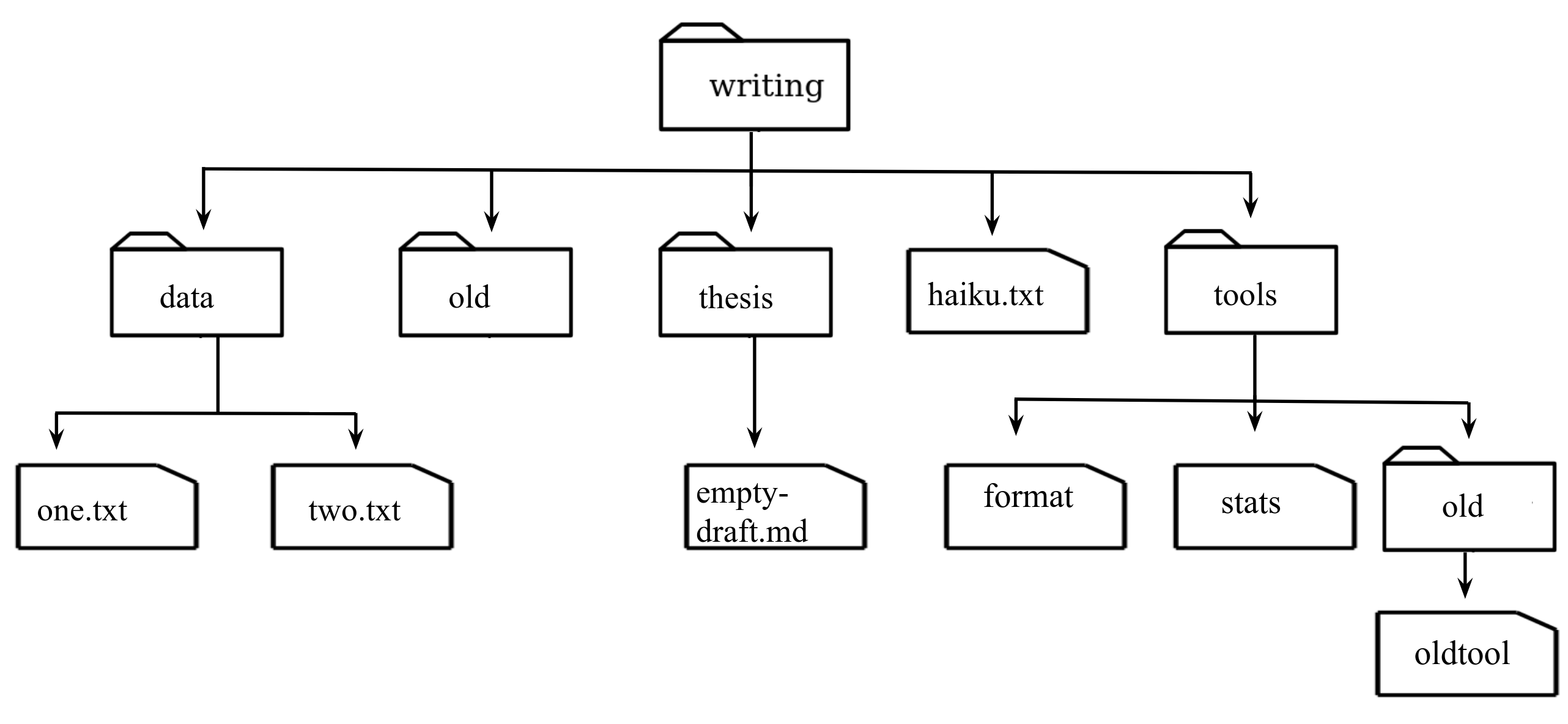

Nelle’s writing directory contains one file called haiku.txt and four subdirectories:

thesis (which contains a sadly empty file, empty-draft.md),

data (which contains two files one.txt and two.txt),

a tools directory that contains the programs format and stats,

and a subdirectory called old, with a file oldtool.

For our first command, let’s run find .:

$ find .

.

./thesis

./thesis/empty-draft.md

./old

./old/.gitkeep

./tools

./tools/format

./tools/old

./tools/old/oldtool

./tools/stats

./haiku.txt

./data

./data/one.txt

./data/two.txt

As always, the . on its own means the current working directory, which is where we want our search to start. find’s output is the names of every file and directory under the current working directory. This can seem useless at first but find has many options to filter the output and in this episode we will discover some of them.

The first option in our list is -type d that means “things that are directories”. Sure enough, find’s output is the names of the five directories in our little tree (including .):

$ find . -type d

.

./thesis

./old

./tools

./tools/old

./data

When using find, note that the order of the results shown may differ depending on whether you’re using Windows or a Mac.

If we change -type d to -type f,

we get a listing of all the files instead:

$ find . -type f

./thesis/empty-draft.md

./old/.gitkeep

./tools/format

./tools/old/oldtool

./tools/stats

./haiku.txt

./data/one.txt

./data/two.txt

find automatically goes into subdirectories,

their subdirectories,

and so on to find everything that matches the pattern we’ve given it.

If we don’t want it to,

we can use -maxdepth to restrict the depth of search:

$ find . -maxdepth 1 -type f

./haiku.txt

The opposite of -maxdepth is -mindepth,

which tells find to only report things that are at or below a certain depth.

-mindepth 2 therefore finds all the files that are two or more levels below us:

$ find . -mindepth 2 -type f

/thesis/empty-draft.md

./old/.gitkeep

./tools/format

./tools/old/oldtool

./tools/stats

./data/one.txt

./data/two.txt

Now let’s try matching by name:

$ find . -name *.txt

./haiku.txt

We expected it to find all the text files,

but it only prints out ./haiku.txt.

The problem is that the shell expands wildcard characters like * before commands run.

Since *.txt in the current directory expands to haiku.txt,

the command we actually ran was:

$ find . -name haiku.txt

find did what we asked; we just asked for the wrong thing.

To get what we want,

let’s do what we did with grep:

put *.txt in single quotes to prevent the shell from expanding the * wildcard.

This way,

find actually gets the pattern *.txt, not the expanded filename haiku.txt:

$ find . -name '*.txt'

./haiku.txt

./data/one.txt

./data/two.txt

Listing vs. Finding

lsandfindcan be made to do similar things given the right options, but under normal circumstances,lslists everything it can, whilefindsearches for things with certain properties and shows them.

Another way to combine command-line tools

As we said earlier, the command line’s power lies in combining tools. We’ve seen how to do that with pipes; let’s explore another technique. In a previous encounter, we introduced the caret (^) character in regular expressions, which typically signifies the beginning of a line. Now, let’s meet its counterpart: the dollar sign ($). While in regular expressions, the dollar sign typically denotes the end of a line, in our command line context, its role takes a different form. This technique involves using $() expression to integrate commands. Let’s apply this technique in practice.

As we just saw, find . -name '*.txt' gives us a list of all text files in or below the current directory. So, how can we combine that with wc -l to count the lines in all those files? The simplest way is to put the find command inside $(). Note that instead of its usual role in regular expressions, the dollar sign now helps define the argument in the parenthesis.

$ wc -l $(find . -name '*.txt')

70 ./data/one.txt

300 ./data/two.txt

11 ./haiku.txt

381 total

When the shell executes this command,

the first thing it does is run whatever is inside the $().

It then replaces the $() expression with that command’s output.

Since the output of find is the three filenames ./data/one.txt, ./data/two.txt, and ./haiku.txt,

the shell constructs the command:

$ wc -l ./data/one.txt ./data/two.txt ./haiku.txt

which is what we wanted.

This expansion is exactly what the shell does when it expands wildcards like * and ?,

but lets us use any command we want as our own “wildcard”.

It’s very common to use find and grep together.

The first finds files that match a pattern;

the second looks for lines inside those files that match another pattern.

Here, for example, we can find PDB files that contain iron atoms

by looking for the string “FE” in all the .pdb files above the current directory:

$ grep "FE" $(find .. -name '*.pdb')

../data/pdb/heme.pdb:ATOM 25 FE 1 -0.924 0.535 -0.518

Binary Files

We have focused exclusively on finding things in text files. What if your data is stored as images, in databases, or in some other format? One option would be to extend tools like

grepto handle those formats. This hasn’t happened, and probably won’t, because there are too many formats to support.The second option is to convert the data to text, or extract the text-ish bits from the data. This is probably the most common approach, since it only requires people to build one tool per data format (to extract information). On the one hand, it makes simple things easy to do. On the negative side, complex things are usually impossible. For example, it’s easy enough to write a program that will extract X and Y dimensions from image files for

grepto play with, but how would you write something to find values in a spreadsheet whose cells contained formulas?The third choice is to recognize that the shell and text processing have their limits, and to use a programming language such as Python instead. When the time comes to do this, don’t be too hard on the shell: many modern programming languages, Python included, have borrowed a lot of ideas from it, and imitation is also the sincerest form of praise.

The Bash shell is older than most of the people who use it. It has survived so long because it is one of the most productive programming environments ever created. Its syntax may be cryptic, but people who have mastered it can experiment with different commands interactively, then use what they have learned to automate their work. Graphical user interfaces may be better at experimentation, but the shell is usually much better at automation. And as Alfred North Whitehead wrote in 1911, “Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.”

Exercises

Using grep

cat haiku.txtThe Tao that is seen Is not the true Tao, until You bring fresh toner. With searching comes loss and the presence of absence: "My Thesis" not found. Yesterday it worked Today it is not working Software is like that.From the above text, contained in the file

haiku.txt, which command would result in the following output:and the presence of absence:

grep "of" haiku.txtgrep -E "of" haiku.txtgrep -w "of" haiku.txtgrep -i "of" haiku.txtSolution

- Incorrect, since it will find lines that contain

ofincluding those that are not a complete word, including “Software is like that.”- Incorrect,

-E(which enables extended regular expressions ingrep), won’t change the behaviour since the given pattern is not a regular expression. So the results will be the same as 1.- Correct, since we have supplied

-wto indicate that we are looking for a complete word, hence only “and the presence of absence:” is found.- Incorrect.

-iindicates we wish to do a case insensitive search which isn’t required. The results are the same as 1.

findpipeline reading comprehensionWrite a short explanatory comment for the following shell script:

find . -name '*.dat' | wc -l | sort -nSolution

Find all files (in this directory and all subdirectories) that have a filename that ends in

.dat, count the number of files found, and sort the result. Note that thesorthere is unnecessary, since it is only sorting one number.

Matching

ose.datbut nottempThe

-vflag togrepinverts pattern matching, so that only lines which do not match the pattern are printed. Given that, which of the following commands will find all files in/datawhose names end inose.dat(e.g.,sucrose.datormaltose.dat), but do not contain the wordtemp?

find /data -name '*.dat' | grep ose | grep -v temp

find /data -name ose.dat | grep -v temp

grep -v "temp" $(find /data -name '*ose.dat')None of the above.

Solution

- Incorrect, since the first

grepwill find all filenames that containosewherever it may occur, and also because the use ofgrepas a following pipe command will only match on filenames output fromfindand not their contents.- Incorrect, since it will only find those files than match

ose.datexactly, and also because the use ofgrepas a following pipe command will only match on filenames output fromfindand not their contents.- Correct answer. It first executes the

findcommand to find those files matching the ‘*ose.dat’ pattern, which will match on exactly those that end inose.dat, and thengrepwill search those files for “temp” and only report those that don’t contain it, since it’s using the-vflag to invert the results.- Incorrect.

Key Points

findfinds files with specific properties that match patterns.

grepselects lines in files that match patterns.

$([command])inserts a command’s output in place.