Scalability Profiling

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How scalable is a particular piece of code?

How can I generate evidence for a code’s scalability?

What does good and bad scalability look like?

Objectives

Explain how Amdahl’s Law can help us understand the scalability of code.

Use Amdahl’s Law to predict the theoretical maximum speedup on some example code when using multiple processors.

Understand strong and weak scaling graphs for some example code.

Describe the graphing characteristics of good and bad scalability.

Let’s now look at how we can determine the scalability characteristics for our example π code.

Characterising our π Code’s Performance

When we ran our π code in a previous episode, we got some timing results for running our code over an increasing number of cores. An example run may look something like:

| Cores (n) | Run Time (s) | Result | Error | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.99667 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | - |

| 2 | 2.064242 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | 1.94 |

| 4 | 1.075068 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | 3.72 |

| 8 | 0.687097 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | 5.82 |

| 16 | 0.349366 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | 11.44 |

As we saw, by using MPI we were able to reduce the run time of our code by using more cores without affecting the results. The new column speedup shown in the table above was calculated using, e.g. with 1 core:

Speedup = T1 / Tn

Where T1 denotes the time taken to run the code with only 1 core, and Tn denotes the time taken to run the code with n cores.

The speedup efficiency, which measures how efficiently the additional resources are being used, is,

Efficiencyn = Speedupn / n,

Which could be as high as 1, but probably will never reach that in practice.

Calculate using your Own Results I

Submit your Pi job again, as you did in the previous episode. e.g. with a job script called

mpi-pi.sh:$ sbatch mpi-pi.shMake a copy of the SLURM output file (i.e. using the

cpcommand) and add aSpeedupcolumn of your own, using the above Speedup formula, for eachnpresult. We’ll use these figures later!Solution

You’ll notice that your own result timings are different from the ones above, and a key reason is that these were run on a working system with other users, so the runtime will be affected depending on the load of the system.

What Type of Scaling?

Looking at your own results, is this an example of strong or weak scaling?

Solution

This is an example of strong scaling, as we are keeping the data sample the same but increasing the number of cores used.

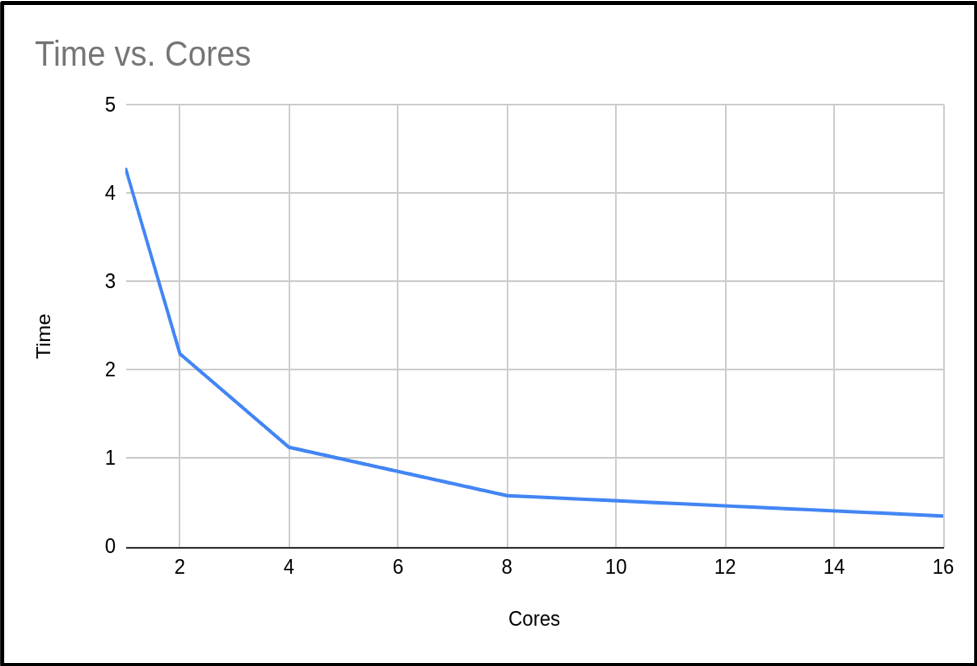

When we plot the run time against the number of cores with the results from the above table, we see the following graph:

So we can see that as the number of cores increases, the run time of our program decreases. This makes sense, since we are splitting the calculation into smaller pieces which are executed at the same time.

Amdahl’s Law

If we use n processors, we might expect n times speedup. But as we’ve mentioned, this is rarely, if ever, the case! In a program, there is always some portion of it which must be executed in serial (such as initialisation routines, I/O operations and inter-communication) which cannot be parallelised. This limits how much a program can be speeded up, as the program will always take at least the length of the serial portion. This is actually known as Amdahl’s Law, which states that a program’s serial parts limit the potential speedup from parallelising the code.

We can think of a program as being operations which can and can’t be parallelised, i.e. the part of the code we can and can’t be speeded up. The time taken for a program to finish executing is the sum of the fractions of time spent in the serial and parallel portion of the code,

Time to Complete (T) = Fraction of time taken in Serial Portion (FS) + Fraction of time taken in Parallel Portion (FP)

T = FS + FP

When a program executes in parallel, the parallel portion of the code is split between the available cores. But since the serial portion is not split in this way, the time to complete is therefore,

Tn = FS + FP / n

We can see that as the number of cores in use increases, then the time to complete decreases until it approaches that of the serial portion. The speedup from using more cores is,

Speedup = T1 / Tn = ( FS + FP ) / ( FS + FP / n )

To simplify the above, we will define the single core execution time as a single unit of time, such that FS + FP = 1.

Speedup = 1 / ( FS + FP / n )

Again this shows us that as the number of cores increases, the serial portion of the code will dominate the run time as when n = ∞,

Max speedup = 1 / FS

What’s the Maximum Speedup?

From the previous section, we know the the maximum speedup achievable is limited to how long a program takes to execute in serial. If we know the portion of time spent in the serial and parallel code, we will theoretically know by how much we can accelerate our program. However, it’s not always simple to know the exact value of these fractions. But from Amdahl’s law, if we can measure the speedup as a function of number of cores, we can estimate that maximum speed up.

We can rearrange Amdahl’s law to estimate the parallel portion FP,

FP = n / ( n - 1 ) ( ( T1 - Tn ) / T1 )

Using the above formula on our example code we get the following results:

| Cores (n) | Tn | Fp | Fs = 1 - Fp |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.99667 | - | - |

| 2 | 2.064242 | 0.967019 | 0.0329809 |

| 4 | 1.075068 | 0.974678 | 0.0253212 |

| 8 | 0.687097 | 0.946380 | 0.0536198 |

| 16 | 0.349366 | 0.973424 | 0.0265752 |

| Average | 0.965375 | 0.0346242 |

We now have an estimated percentage for our serial and parallel portion of our code. As you can see, as the number of cores we use increases, the time spent in the serial portion of the code increases.

Calculate using your Own Results II

Looking back at your own results from the previous Calculate using your Own Results I exercise, create new columns for Fp and Fs and calculate the results for each, using the formula above. Finally, calculate the average for each of these as in the table above.

Differences in Serial Timings

Similarly, in this instance we see that serial run times may vary depending on the run. There are several factors that are impacting our code. Firstly as we’ve discussed, these were run on a working system with other users, so runtime will be affected depending on the load of the system. Throughout DiRAC, it is normal when you run your code to have exclusive access, so this will be less of an issue. But if, for example, your code accesses bulk storage then there may be an impact since these are shared resources. As we are using the MPI library in our code, it would be expected that the serial portion will actually increase slightly with the number of cores due to additional MPI overheads. This will have a noticeable impact if you try scaling your code into the thousands of cores.

If we have several values, we can take the average to estimate an upper bound on how much benefit we will get from adding more processors. In our case then, the maximum speedup we can expect is,

Max speedup = 1 / FS = 1 / ( 1 - FP ) = 1 / ( 1 - 0.965375 ) = 29

Using this formula we can calculate a table of the expected maximum speedup for a given FP:

| FP | Max Speedup |

|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.00 |

| 0.1 | 1.11 |

| 0.2 | 1.25 |

| 0.3 | 1.43 |

| 0.4 | 1.67 |

| 0.5 | 2.00 |

| 0.6 | 2.50 |

| 0.7 | 3.33 |

| 0.8 | 5.00 |

| 0.9 | 10.00 |

| 0.95 | 20.00 |

| 0.99 | 100.00 |

Number of Cores vs Expected Speedup

Using what we’ve learned about Amdahl’s Law and the average percentages of serial and parallel proportions of our example code we calculated earlier in the Calculate using your Own Results II exercise, fill in or create a table estimating the expected total speedup and change in speedup when doubling the number of cores, in a table like the following (with the number of cores doubling each time until a total of 4096). Substitute the initial T1

???????value with the initial Tn value from your own run.Hints: use the following formula:

Tn = Fs + ( Fp / n )

Speedup = T1 / Tn

Cores (n) Tn Speedup Change in Speedup 1 ??????? 2 4 … 4096 When does the change in speedup drop below 1%?

Solution

How closely do these estimations correlate with your actual results to 16 cores? They should hopefully be similar, since we’re working off averages for our serial and parallel proportions.

Hopefully from your results you will find that we can get close to the maximum speedup calculated earlier, but it requires ever more resources. From our own trial runs, we expect the speedup to drop below 1% at 4096 cores, but it is expected that we would never run this code at these core counts as it would be a waste of resources.

Using the

3.9967T1 starting value, we get the following estimations:

Cores (n) Tn Speedup Change in Speedup 1 3.99667 1 0 2 2.067504 1.933089 0.933089 4 1.102943 3.623642 1.690553 8 0.620662 6.439365 2.815723 16 0.379522 10.530804 4.091439 32 0.258952 15.434038 4.903234 64 0.198667 20.117475 4.683437 128 0.168524 23.715726 3.598251 256 0.153453 26.044951 2.329225 512 0.145917 27.389997 1.345046 1024 0.142149 28.115998 0.726001 2048 0.140265 28.493625 0.377627 4096 0.139323 28.686268 0.192643

How Many Cores Should we Use?

From the data you have just calculated, what do you think the maximum number of cores we should use with our code to balance reduced execution time versus efficient usage of compute resources.?

Solution

Within DiRAC we do not impose such a limit, this is a decision made by you. Every project has an allocation and it is up to you to decide what is efficient use of your allocation. In this case I personally would not waste my allocation on any runs over 128 cores.

Calculating a Weak Scaling Profile

Not all codes are suited to strong scaling. As seen in the previous example, even codes with as much as 96% parallelizable code will hit limits. Can we do something to enable moderately parallelizable codes to access the power of HPC systems? The answer is yes, and is demonstrated through weak scaling.

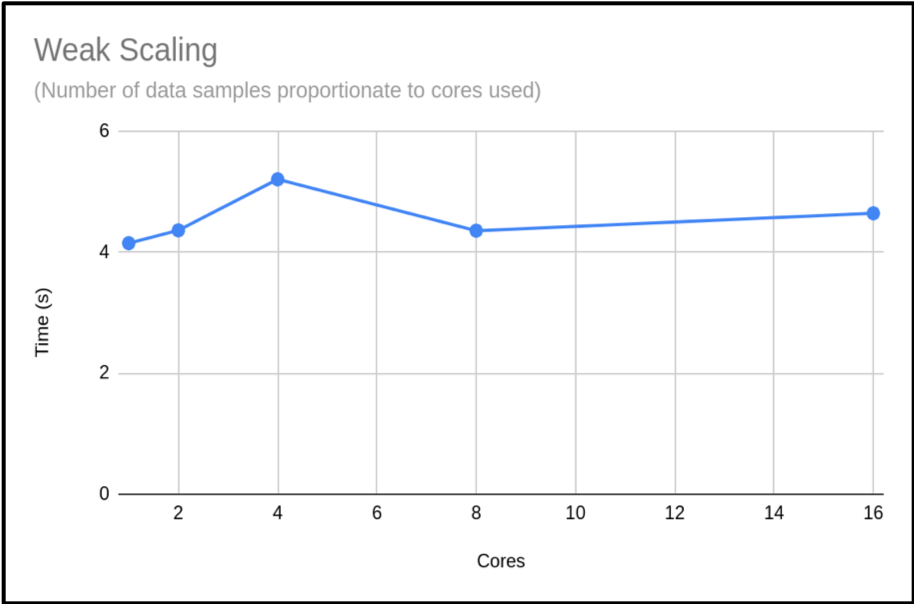

The problem with strong scaling is as we increase the number of cores, then the relative size of the parallel portion of our task reduces until it is negligible, and then we can not go any further. The solution is to increase the problem size as you increase the core count – this is Gustafson’s law. This method tries to keep the proportion of serial time and parallel time the same. We will not get the benefit of reduced time for our calculation, but we will have the benefit of processing more data. Below is a re-run of our π code. But this time, as we increase the cores we also increase the samples used to calculate π.

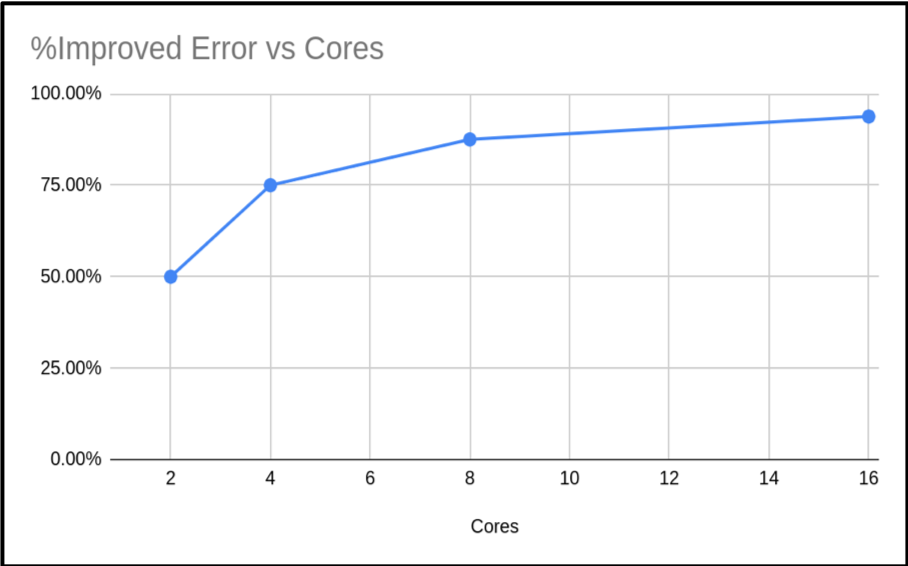

| Cores (n) | Run Time | Result | Error | % Improved Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.149807 | 3.14159265459 | 0.00000003182 | |

| 2 | 4.362416 | 3.14159265409 | 0.00000001591 | 50.00% |

| 4 | 5.205988 | 3.14159265384 | 0.00000000795 | 75.02% |

| 8 | 4.356564 | 3.14159265371 | 0.00000000397 | 87.52% |

| 16 | 4.643724 | 3.14159265365 | 0.00000000198 | 93.78% |

As you can see, the run times are similar. Just slightly increasing. However, the accuracy of the calculated value of π has increased. In fact our percentage improvement is nearly in step with the number of cores.

When presenting your weak scaling it is common to show how well it scales, this is shown below:

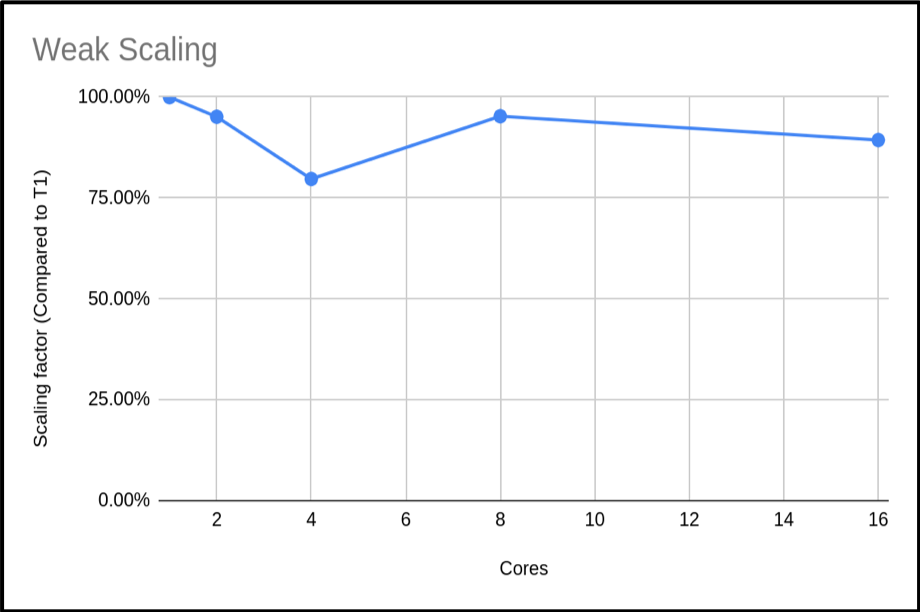

We can also plot the scaling factor. This is the percentage increase in run time compared to base run time for a normal run. In this case we are just using T1:

The above plot shows that the code is highly scalable. We do have an anomaly with our 4 core run, however. It would be good to rerun this to get a more representative sample, but this result is a common occurrence when using shared systems. In this example we only did a single run for each core count. When compiling your data for presentation or submitting applications, it would be better to do many runs and exclude outlying data samples or provide an uncertainty estimate.

Calculate using your Own Results III

You can reproduce this weak scaling profile with the Pi code by submitting a job which executes the following instead, in

mpi-pi.sh:... ./run.sh WeakBy passing this argument, our program is able to provide timings for a weak profile, scaling up the required accuracy for Pi accordingly. Make this amendment, and see how your results compare.

Maximum Cores to Use?

It would be hard to estimate the max cores we could use from this plot. Can you suggest an approach to get a clearer picture of this code’s weak scaling profile?

Solution

The obvious answer is to do more runs with higher core counts, and also try to resolve the n = 4 sample. This should give you a clearer picture of the weak scaling profile.

Obtaining Resources to Profile your Code

It may be difficult to profile your code if you do not have the resources at hand, but DiRAC can help. If you are in a position of wanting to use DiRACs facilities but do not have the resources to profile your code, then you can apply for a Seedcorn project. This is a short project with up to 100,000 core hours for you to profile and possibly improve your code before applying for a large allocation of time.

Key Points

We can use Amdahl’s Law to understand the expected speedup of a parallelised program against multiple cores.

It’s often difficult to estimate the proportion of serial code in our programs, but a reformulation of Amdahl’s Law can give us this based on multiple runs against a different number of cores.

Run timings for serial code can vary due to a number of factors such as overall system load and accessing shared resources such as bulk storage.

The Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard is a common way to parallelise code and is available on many platforms and HPC systems, including DiRAC.

When calculating a strong scaling profile, the additional benefit of adding cores decreases as the number of cores increases.

The limitation of strong scaling is the fixed problem size, and we can increase the problem size with the core count to obtain a weak scaling profile.