Introduction to Parallelisation

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What is parallelisation?

Why is parallel programming important?

What are the different types of parallelism?

What are the common challenges in parallel programming?

Objectives

Understand the concept of parallelisation and its significance in improving performance.

Explore different types of parallelism, including shared memory parallelism.

Gain familiarity with the basics of OpenMP and how it enables shared memory parallelism.

Parallelisation is a technique that allows us to divide a complex computational task into smaller subtasks, enabling simultaneous execution and improving performance while reducing execution times. In this course, you will learn how to design parallel algorithms and write parallel programs using OpenMP. OpenMP, an abbreviation for “Open Multi-Processing,” is an application programming interface (API) that supports parallel programming in C, C++, and Fortran. It simplifies the development of multithreaded programs by incorporating compiler directives, library routines, and environment variables in a simple and portable manner. However, before we dive into programming with OpenMP, let’s establish a strong foundation by exploring key concepts that are essential to parallel programming. These concepts will provide us with the necessary knowledge and understanding as we progress through the upcoming episodes.

Parallelisation in A Nutshell

At some point in your career, you’ve probably asked the question “How can I make my code run faster?”. Of course, the answer to this question will depend sensitively on your specific situation, but here are a few approaches you might try doing:

- Optimize the code.

- Move computationally demanding parts of the code from an interpreted language (Python, Ruby, etc.) to a compiled language (C/C++, Fortran, Julia, Rust, etc.).

- Use better theoretical methods that require less computation for the same accuracy.

Each of the above approaches is intended to reduce the total amount of work required by the computer to run your code. A different strategy for speeding up codes is parallelisation, in which you split the computational work among multiple processing units that labor simultaneously. The “processing units” might include central processing units (CPUs), graphics processing units (GPUs), vector processing units (VPUs), or something similar.

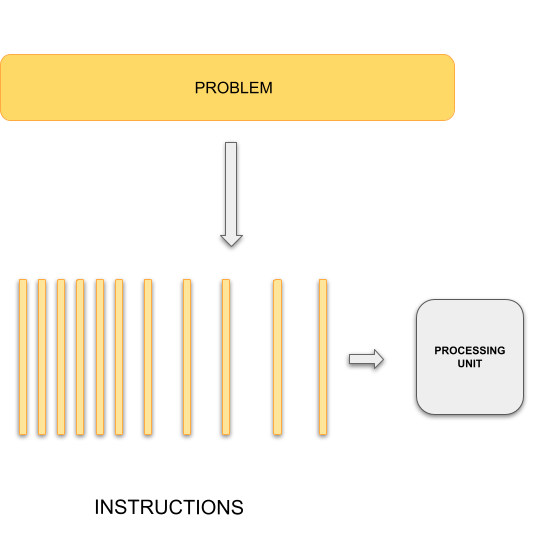

Sequential Computing

|

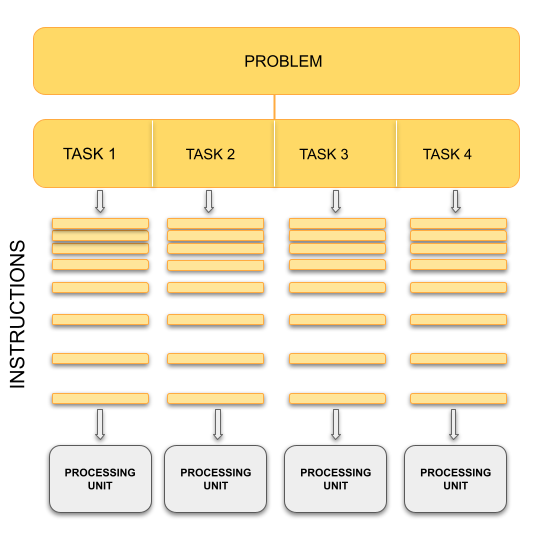

Parallel Computing

|

In general, typical programming assumes that computers execute one operation at a time in the sequence specified by your program code. At any time step, the computer’s CPU core will be working on one particular operation from the sequence. In other words, a problem is broken into discrete series of instructions that are executed one for another. Therefore only one instruction can execute at any moment in time. We will call this traditional style of sequential computing.

In contrast, with parallel computing we will now be dealing with multiple CPU cores that each are independently and simultaneously working on a series of instructions. This can allow us to do much more at once, and therefore get results more quickly than if only running an equivalent sequential program. The act of changing sequential code to parallel code is called parallelisation.

Analogy

The basic concept of parallel computing is simple to understand: we divide our job in tasks that can be executed at the same time so that we finish the job in a fraction of the time that it would have taken if the tasks are executed one by one.

Suppose that we want to paint the four walls in a room. This is our problem. We can divide our problem in 4 different tasks: paint each of the walls. In principle, our 4 tasks are independent from each other in the sense that we don’t need to finish one to start another. However, this does not mean that the tasks can be executed simultaneously or in parallel. It all depends on on the amount of resources that we have for the tasks.

If there is only one painter, they could work for a while in one wall, then start painting another one, then work a little bit on the third one, and so on. The tasks are being executed concurrently but not in parallel and only one task is being performed at a time. If we have 2 or more painters for the job, then the tasks can be performed in parallel.

Key idea

In our analogy, the painters represent CPU cores in the computers. The number of CPU cores available determines the maximum number of tasks that can be performed in parallel. The number of concurrent tasks that can be started at the same time, however is unlimited.

Splitting the problem into computational tasks across different processors and running them all at once may conceptually seem like a straightforward solution to achieve the desired speed-up in problem-solving. However, in practice, parallel programming involves more than just task division and introduces various complexities and considerations.

Let’s consider a scenario where you have a single CPU core, associated RAM (primary memory for faster data access), hard disk (secondary memory for slower data access), input devices (keyboard, mouse), and output devices (screen).

Now, imagine having two or more CPU cores. Suddenly, you have several new factors to take into account:

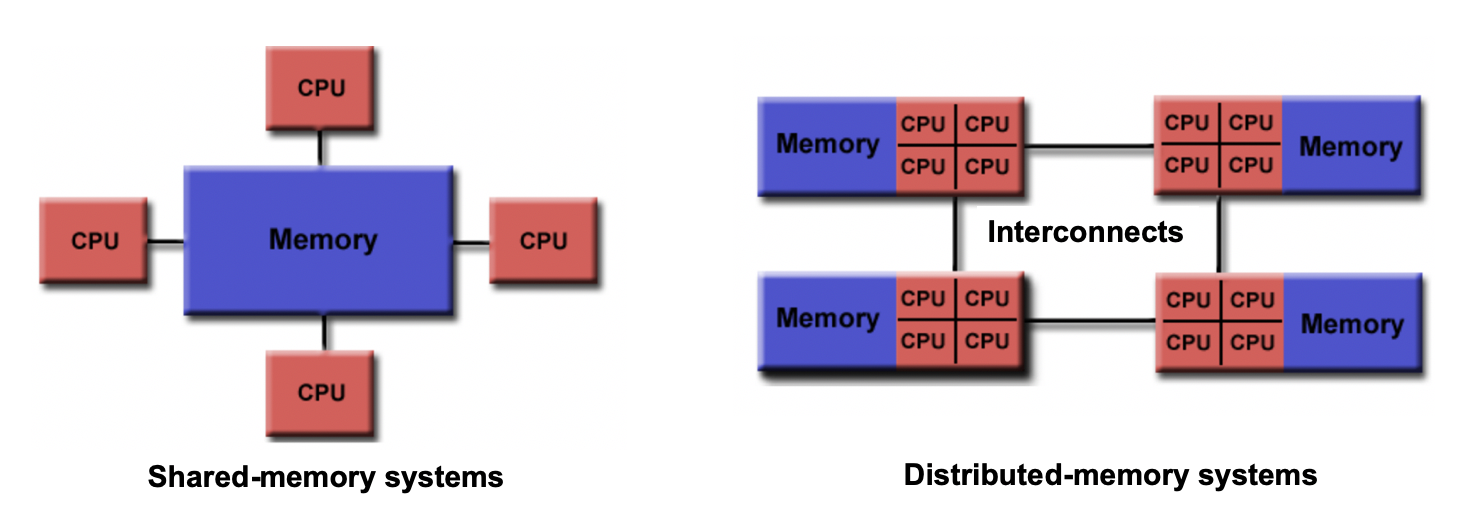

- If there are two cores, there are two possibilities: either these cores share the same RAM (shared memory) or each core has its own dedicated RAM (private memory).

- In the case of shared memory, what happens when two cores try to write to the same location simultaneously? This can lead to a race condition, which requires careful handling by the programmer to avoid conflicts.

- How do we divide and distribute the computational tasks among these cores? Ensuring a balanced workload distribution is essential for optimal performance.

- Communication between cores becomes a crucial consideration. How will the cores exchange data and synchronize their operations? Effective communication mechanisms must be established.

- After completing the tasks, where should the final results be stored? Should they reside in the storage of Core 1, Core 2, or a central storage accessible to both? Additionally, which core is responsible for displaying output on the screen?

These considerations highlight the interplay between parallel programming and memory. To efficiently utilize multiple CPU cores, we need to understand the different memory models—shared memory and distributed memory- as well as the concepts of processes and threads that form the foundation of parallel computing that play a crucial role in achieving optimal parallel execution.

To address the challenges that arise when parallelising programs across multiple cores and achieve efficient use of available resources, parallel programming frameworks like OpenMP and MPI (Message Passing Interface) come into play. These frameworks provide tools, libraries, and methodologies to handle memory management, workload distribution, communication, and synchronization in parallel environments.

Now, let’s take a brief look at these fundamental concepts and explore the differences between OpenMP and MPI, setting the stage for a deeper understanding of OpenMP for the next episode.

Shared vs Distributed Memory

Shared memory refers to a memory model where multiple processors can directly access and modify the same memory space. Changes made by one processor are immediately visible to all other processors. Shared memory programming models, like OpenMP, simplify parallel programming by providing mechanisms for sharing and synchronizing data.

Distributed memory, on the other hand, involves memory resources that are physically separated across different computers or nodes in a network. Each processor has its own private memory, and explicit communication is required to exchange data between processors. Distributed memory programming models, such as MPI, facilitate communication and synchronization in this memory model.

The choice between shared memory and distributed memory models depends on the nature of the problem and the available computing resources. Shared memory parallelism is well-suited for problems that can be efficiently divided into smaller tasks and where the coordination and communication overhead are relatively low. Distributed memory parallelism shines in scenarios where the problem size exceeds the capabilities of a single machine, and computation needs to be distributed across multiple nodes.

Differences/Advantages/Disadvantages of Shared and Distributed Memory

- Accessibility: Shared memory allows direct access to the same memory space by all processors, while distributed memory requires explicit communication for data exchange between processors.

- Memory Scope: Shared memory provides a global memory space, enabling easy data sharing and synchronization. In distributed memory, each processor has its own private memory space, requiring explicit communication for data sharing.

- Memory Consistency: Shared memory ensures immediate visibility of changes made by one processor to all other processors. Distributed memory requires explicit communication and synchronization to maintain data consistency across processors.

- Scalability: Shared memory systems are typically limited to a single computer or node, whereas distributed memory systems can scale to larger configurations with multiple computers and nodes.

- Programming Complexity: Shared memory programming models offer simpler constructs and require less explicit communication compared to distributed memory models. Distributed memory programming involves explicit data communication and synchronization, adding complexity to the programming process.

Analogy

Imagine that all workers have to obtain their paint from a central dispenser located at the middle of the room. If each worker is using a different colour, then they can work asynchronously. However, if they use the same colour, and two of them run out of paint at the same time, then they have to synchronise to use the dispenser — one should wait while the other is being serviced.

Now let’s assume that we have 4 paint dispensers, one for each worker. In this scenario, each worker can complete their task totally on their own. They don’t even have to be in the same room, they could be painting walls of different rooms in the house, in different houses in the city, and different cities in the country. We need, however, a communication system in place. Suppose that worker A, for some reason, needs a colour that is only available in the dispenser of worker B, they must then synchronise: worker A must request the paint of worker B and worker B must respond by sending the required colour.

Key Idea

In our analogy, the paint dispenser represents access to the memory in your computer. Depending on how a program is written, access to data in memory can be synchronous or asynchronous. For the different dispensers case for your workers, however, think of the memory distributed on each node/computer of a cluster.

Processes

A process refers to an individual running instance of a software program. Each process operates independently and possesses its own set of resources, such as memory space and open files. As a result, data within one process remains isolated and cannot be directly accessed by other processes.

In parallel programming, the objective is to achieve parallel execution by simultaneously running coordinated processes. This naturally introduces the need for communication and data sharing among them. To facilitate this, parallel programming models like MPI come into effect. MPI provides a comprehensive set of libraries, tools, and methodologies that enable processes to exchange messages, coordinate actions, and share data, enabling parallel execution across a cluster or network of machines.

Threads

A thread is an execution unit within a process. Unlike processes, threads operate within the context of a single process and share the same memory and resources. Threads can be thought of as separate points of execution within a program, capable of performing tasks concurrently.

In a single-threaded program, there is only one thread of execution within a process and it follows a sequential flow, where each instruction is executed one after another. In a multi-threaded program, however, multiple threads of execution exist within a single process. These threads can access and share the same data and resources, enabling more efficient and faster parallel programming.

One advantage of using threads is that they can be easier to work with compared to processes when it comes to parallel programming. When incorporating threads, especially with frameworks like OpenMP, modifying a program becomes simpler. This ease of use stems from the fact that threads operate within the same process and can directly access shared data, eliminating the need for complex inter-process communication mechanisms required by MPI. However, it’s important to note that threads within a process are limited to a single computer. While they provide an effective means of utilizing multiple CPU cores on a single machine, they cannot extend beyond the boundaries of that computer.

Analogy

Let’s go back to our painting 4 walls examples with a team of workers. Each painter represents a “process” (an individual instance of a program), and they share the same painting tools and materials. Now, let’s focus on the painters’ arms. Each arm can be seen as a “thread”, capable of performing independent actions and working on different sections of the wall simultaneously. Just as the painters coordinate their movements to avoid conflicts and overlap, threads in a program coordinate their execution to ensure synchronization and efficient use of shared resources.

In our painting analogy, a single-threaded program can be compared to a single painter working alone to paint the walls of a room. The painter performs each stroke of the brush in a sequential manner, completing the painting task step by step.

Now, let’s introduce the concept of multiple threads within a process. In our painting analogy, imagine the team of painters expanding their operations. Each painter still represents a process, but now they have multiple threads of execution represented by their arms. Each arm can work independently, allowing different sections of the wall to be painted simultaneously.

Parallel Paradigms

Thinking back to shared vs distributed memory models, how to achieve a parallel computation is divided roughly into two paradigms. Let’s set both of these in context:

- In a shared memory model, a data parallelism paradigm is typically used, as employed by OpenMP: the same operations are performed simultaneously on data that is shared across each parallel operation. Parallelism is achieved by how much of the data a single operation can act on.

- In a distributed memory model, a message passing paradigm is used, as employed by MPI: each CPU (or core) runs an independent program. Parallelism is achieved by receiving data which it doesn’t have, conducting some operations on this data, and sending data which it has.

This division is mainly due to historical development of parallel architectures: the first one follows from shared memory architecture like SMP (Shared Memory Processors) and the second from distributed computer architecture. A familiar example of the shared memory architecture is GPU (or multi-core CPU) architecture, and an example of the distributed computing architecture is a cluster of distributed computers. Which architecture is more useful depends on what kind of problems you have. Sometimes, one has to use both!

Consider a simple loop which can be sped up if we have many cores for illustration:

for(i=0; i<N; i++) {

a[i] = b[i] + c[i];

}

If we have N or more cores, each element of the loop can be computed in

just one step (for a factor of \(N\) speed-up). Let’s look into both paradigms in a little more detail, and focus on key characteristics.

1. Data Parallelism Paradigm

To understand what data parallelism means, let’s consider the following bit of OpenMP code which parallelizes the above loop:

#pragma omp parallel for for(i=0; i<N; i++) { a[i] = b[i] + c[i]; }Parallelization achieved by just one additional line,

#pragma omp parallel for, handled by the preprocessor in the compile stage, where the compiler “calculates” the data address off-set for each core and lets each one compute on a part of the whole data. This approach provides a convenient abstraction, and hides the underlying parallelisation mechanisms.Here, the catch word is shared memory which allows all cores to access all the address space. We’ll be looking into OpenMP later in this course. In Python, process-based parallelism is supported by the multiprocessing module.

2. Message Passing Paradigm

In the message passing paradigm, each processor runs its own program and works on its own data. To work on the same problem in parallel, they communicate by sending messages to each other. Again using the above example, each core runs the same program over a portion of the data. For example, using this paradigm to parallelise the above loop instead:

for(i=0; i<m; i++) { a[i] = b[i] + c[i]; }

- Other than changing the number of loops from

Ntom, the code is exactly the same.mis the reduced number of loops each core needs to do (if there areNcores,mis 1 (=N/N)). But the parallelization by message passing is not complete yet. In the message passing paradigm, each core operates independently from the other cores. So each core needs to be sent the correct data to compute, which then returns the output from that computation. However, we also need a core to coordinate the splitting up of that data, send portions of that data to other cores, and to receive the resulting computations from those cores.Summary

In the end, both data parallelism and message passing logically achieve the following:

Therefore, each rank essentially operates on its own set of data, regardless of paradigm. In some cases, there are advantages to combining data parallelism and message passing methods together, e.g. when there are problems larger than one GPU can handle. In this case, data parallelism is used for the portion of the problem contained within one GPU, and then message passing is used to employ several GPUs (each GPU handles a part of the problem) unless special hardware/software supports multiple GPU usage.

Algorithm Design

Designing a parallel algorithm that determines which of the two paradigms above one should follow rests on the actual understanding of how the problem can be solved in parallel. This requires some thought and practice.

To get used to “thinking in parallel”, we discuss “Embarrassingly Parallel” (EP) problems first and then we consider problems which are not EP problems.

Embarrassingly Parallel Problems

Problems which can be parallelized most easily are EP problems, which occur in many Monte Carlo simulation problems and in many big database search problems. In Monte Carlo simulations, random initial conditions are used in order to sample a real situation. So, a random number is given and the computation follows using this random number. Depending on the random number, some computation may finish quicker and some computation may take longer to finish. And we need to sample a lot (like a billion times) to get a rough picture of the real situation. The problem becomes running the same code with a different random number over and over again! In big database searches, one needs to dig through all the data to find wanted data. There may be just one datum or many data which fit the search criterion. Sometimes, we don’t need all the data which satisfies the condition. Sometimes, we do need all of them. To speed up the search, the big database is divided into smaller databases, and each smaller databases are searched independently by many workers!

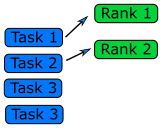

Queue Method

Each worker will get tasks from a predefined queue (a random number in a Monte Carlo problem and smaller databases in a big database search problem). The tasks can be very different and take different amounts of time, but when a worker has completed its tasks, it will pick the next one from the queue.

In an MPI code, the queue approach requires the ranks to communicate what they are doing to all the other ranks, resulting in some communication overhead (but negligible compared to overall task time).

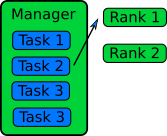

Manager / Worker Method

The manager / worker approach is a more flexible version of the queue method. We hire a manager to distribute tasks to the workers. The manager can run some complicated logic to decide which tasks to give to a worker. The manager can also perform any serial parts of the program like generating random numbers or dividing up the big database. The manager can become one of the workers after finishing managerial work.

In an MPI implementation, the main function will usually contain an

ifstatement that determines whether the rank is the manager or a worker. The manager can execute a completely different code from the workers, or the manager can execute the same partial code as the workers once the managerial part of the code is done. It depends on whether the managerial load takes a lot of time to finish or not. Idling is a waste in parallel computing!Because every worker rank needs to communicate with the manager, the bandwidth of the manager rank can become a bottleneck if administrative work needs a lot of information (as we can observe in real life). This can happen if the manager needs to send smaller databases (divided from one big database) to the worker ranks. This is a waste of resources and is not a suitable solution for an EP problem. Instead, it’s better to have a parallel file system so that each worker rank can access the necessary part of the big database independently.

General Parallel Problems (Non-EP Problems)

In general not all the parts of a serial code can be parallelized. So, one needs to identify which part of a serial code is parallelizable. In science and technology, many numerical computations can be defined on a regular structured data (e.g., partial differential equations in a 3D space using a finite difference method). In this case, one needs to consider how to decompose the domain so that many cores can work in parallel.

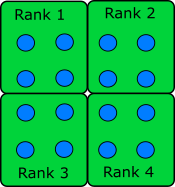

Domain Decomposition

When the data is structured in a regular way, such as when simulating atoms in a crystal, it makes sense to divide the space into domains. Each rank will handle the simulation within its own domain.

Many algorithms involve multiplying very large matrices. These include finite element methods for computational field theories as well as training and applying neural networks. The most common parallel algorithm for matrix multiplication divides the input matrices into smaller submatrices and composes the result from multiplications of the submatrices. If there are four ranks, the matrix is divided into four submatrices.

\[A = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}A_{11} & A_{12} \\ A_{21} & A_{22}\end{array} \right]\] \[B = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}B_{11} & B_{12} \\ B_{21} & B_{22}\end{array} \right]\] \[A \cdot B = \left[ \begin{array}{cc}A_{11} \cdot B_{11} + A_{12} \cdot B_{21} & A_{11} \cdot B_{12} + A_{12} \cdot B_{22} \\ A_{21} \cdot B_{11} + A_{22} \cdot B_{21} & A_{21} \cdot B_{12} + A_{22} \cdot B_{22}\end{array} \right]\]If the number of ranks is higher, each rank needs data from one row and one column to complete its operation.

Load Balancing

Even if the data is structured in a regular way and the domain is decomposed such that each core can take charge of roughly equal amounts of the sub-domain, the work that each core has to do may not be equal. For example, in weather forecasting, the 3D spatial domain can be decomposed in an equal portion. But when the sun moves across the domain, the amount of work is different in that domain since more complicated chemistry/physics is happening in that domain. Balancing this type of loads is a difficult problem and requires a careful thought before designing a parallel algorithm.

Serial and Parallel Regions

Identify the serial and parallel regions in the following algorithm:

vector_1[0] = 1; vector_1[1] = 1; for i in 2 ... 1000 vector_1[i] = vector_1[i-1] + vector_1[i-2]; for i in 0 ... 1000 vector_2[i] = i; for i in 0 ... 1000 vector_3[i] = vector_2[i] + vector_1[i]; print("The sum of the vectors is.", vector_3[i]);Solution

serial | vector_0[0] = 1; | vector_1[1] = 1; | for i in 2 ... 1000 | vector_1[i] = vector_1[i-1] + vector_1[i-2]; parallel | for i in 0 ... 1000 | vector_2[i] = i; parallel | for i in 0 ... 1000 | vector_3[i] = vector_2[i] + vector_1[i]; | print("The sum of the vectors is.", vector_3[i]); The first and the second loop could also run at the same time.In the first loop, every iteration depends on data from the previous two. In the second two loops, nothing in a step depends on any of the other steps, and therefore can be parallelised.

Key Points

Parallelization involves dividing complex computational tasks into smaller subtasks that can be executed simultaneously, leading to improved performance and reduced execution times.

Parallel programming enables algorithms to leverage parallel hardware architectures, such as multi-core CPUs and GPUs, to achieve faster computations.

OpenMP is an essential parallel programming API that simplifies the development of multithreaded programs by incorporating compiler directives, library routines, and environment variables in a portable manner.

Shared memory parallelism is a fundamental concept in OpenMP, where threads share memory and work together to solve computational problems effectively.