Communicating Data in MPI

Overview

Teaching: 15 min

Exercises: 5 minQuestions

How do I exchange data between MPI ranks?

Objectives

Differentiate between point-to-point and collective communication

List basic MPI data types

Describe the role of a communicator

List the communication modes for sending and receiving data

Differentiate between blocking and non-blocking communication

Describe and list possible causes of deadlock

In previous episodes we’ve seen that when we run an MPI application, multiple independent processes are created which do their own work, on their own data, in their own private memory space. At some point in our program, one rank will probably need to know about the data another rank has, such as when combining a problem back together which was split across ranks. Since each rank’s data is private to itself, we can’t just access another rank’s memory and get what we need from there. We have to instead explicitly communicate data between ranks. Sending and receiving data between ranks form some of the most basic building blocks in any MPI application, and the success of your parallelisation often relies on how you communicate data.

Communicating data using messages

MPI is a framework for passing data and other messages between independently running processes. If we want to share or access data from one rank to another, we use the MPI API to transfer data in a “message.” A message is a data structure which contains the data we want to send, and is usually expressed as a collection of data elements of a particular data type.

Sending and receiving data can happen happen in two patterns. We either want to send data from one specific rank to another, known as point-to-point communication, or to/from multiple ranks all at once to a single or multiples targets, known as collective communication. Whatever we do, we always have to explicitly “send” something and to explicitly “receive” something. Data communication can’t happen by itself. A rank can’t just get data from one rank, and ranks don’t automatically send and receive data. If we don’t program in data communication, data isn’t exchanged. Unfortunately, none of this communication happens for free, either. With every message sent, there is an overhead which impacts the performance of your program. Often we won’t notice this overhead, as it is usually quite small. But if we communicate large data or small amounts too often, those (small) overheads add up into a noticeable performance hit.

To get an idea of how communication typically happens, imagine we have two ranks: rank A and rank B. If rank A wants to send data to rank B (e.g., point-to-point), it must first call the appropriate MPI send function which typically (but not always, as we’ll find out later) puts that data into an internal buffer; known as the send buffer or the envelope. Once the data is in the buffer, MPI figures out how to route the message to rank B (usually over a network) and then sends it to B. To receive the data, rank B must call a data receiving function which will listen for messages being sent to it. In some cases, rank B will then send an acknowledgement to say that the transfer has finished, similar to read receipts in e-mails and instant messages.

Check your understanding

Consider a simulation where each rank calculates the physical properties for a subset of cells on a very large grid of points. One step of the calculation needs to know the average temperature across the entire grid of points. How would you approach calculating the average temperature?

Solution

There are multiple ways to approach this situation, but the most efficient approach would be to use collective operations to send the average temperature to a main rank which performs the final calculation. You can, of course, also use a point-to-point pattern, but it would be less efficient, especially with a large number of ranks.

If the simulation wasn’t done in parallel, or was instead using shared-memory parallelism, such as OpenMP, we wouldn’t need to do any communication to get the data required to calculate the average.

MPI data types

When we send a message, MPI needs to know the size of the data being transferred. The size is not the number of bytes of data being sent, as you may expect, but is instead the number of elements of a specific data type being sent. When we send a message, we have to tell MPI how many elements of “something” we are sending and what type of data it is. If we don’t do this correctly, we’ll either end up telling MPI to send only some of the data or try to send more data than we want! For example, if we were sending an array and we specify too few elements, then only a subset of the array will be sent or received. But if we specify too many elements, than we are likely to end up with either a segmentation fault or undefined behaviour! And the same can happen if we don’t specify the correct data type.

There are two types of data type in MPI: “basic” data types and derived data types. The basic data types are in essence

the same data types we would use in C such as int, float, char and so on. However, MPI doesn’t use the same

primitive C types in its API, using instead a set of constants which internally represent the data types. These data

types are in the table below:

| MPI basic data type | C equivalent |

|---|---|

| MPI_SHORT | short int |

| MPI_INT | int |

| MPI_LONG | long int |

| MPI_LONG_LONG | long long int |

| MPI_UNSIGNED_CHAR | unsigned char |

| MPI_UNSIGNED_SHORT | unsigned short int |

| MPI_UNSIGNED | unsigned int |

| MPI_UNSIGNED_LONG | unsigned long int |

| MPI_UNSIGNED_LONG_LONG | unsigned long long int |

| MPI_FLOAT | float |

| MPI_DOUBLE | double |

| MPI_LONG_DOUBLE | long double |

| MPI_BYTE | char |

Remember, these constants aren’t the same as the primitive types in C, so we can’t use them to create variables, e.g.,

MPI_INT my_int = 1;

is not valid code because, under the hood, these constants are actually special data structures used by MPI. Therefore we can only them as arguments in MPI functions.

Don’t forget to update your types

At some point during development, you might change an

intto alongor afloatto adouble, or something to something else. Once you’ve gone through your codebase and updated the types for, e.g., variable declarations and function arguments, you must do the same for MPI functions. If you don’t, you’ll end up running into communication errors. It could be helpful to define compile-time constants for the data types and use those instead. If you ever do need to change the type, you would only have to do it in one place, e.g.:// define constants for your data types #define MPI_INT_TYPE MPI_INT #define INT_TYPE int // use them as you would normally INT_TYPE my_int = 1;

Derived data types, on the other hand, are very similar to C structures which we define by using the basic MPI data types. They’re often useful to group together similar data in communications, or when you need to send a structure from one rank to another. This will be covered in more detail in the Advanced Communication Techniques episode.

What type should you use?

For the following pieces of data, what MPI data types should you use?

a[] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};a[] = {1.0, -2.5, 3.1456, 4591.223, 1e-10};a[] = "Hello, world!";Solution

The fact that

a[]is an array does not matter, because all of the elemnts ina[]will be the same data type. In MPI, as we’ll see in the next episode, we can either send a single value or multiple values (in an array).

MPI_INTMPI_DOUBLE-MPI_FLOATwould not be correct asfloat’s contain 32 bits of data whereasdouble’s are 64 bit.MPI_BYTEorMPI_CHAR- you may want to use strlen to calculate how many elements ofMPI_CHARbeing sent

Communicators

All communication in MPI is handled by something known as a communicator. We can think of a communicator as being a

collection of ranks which are able to exchange data with one another. What this means is that every communication

between two (or more) ranks is linked to a specific communicator. When we run an MPI application, every rank will belong

to the default communicator known as MPI_COMM_WORLD. We’ve seen this in earlier episodes when, for example, we’ve used

functions like MPI_Comm_rank() to get the rank number,

int my_rank;

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &my_rank); // MPI_COMM_WORLD is the communicator the rank belongs to

In addition to MPI_COMM_WORLD, we can make sub-communicators and distribute ranks into them. Messages can only be sent

and received to and from the same communicator, effectively isolating messages to a communicator. For most applications,

we usually don’t need anything other than MPI_COMM_WORLD. But organising ranks into communicators can be helpful in

some circumstances, as you can create small “work units” of multiple ranks to dynamically schedule the workload, create

one communicator for each physical hardware node on a HPC cluster, or to help compartmentalise the problem into smaller

chunks by using a virtual cartesian topology.

Throughout this course, we will stick to using MPI_COMM_WORLD.

Communication modes

When sending data between ranks, MPI will use one of four communication modes: synchronous, buffered, ready or standard. When a communication function is called, it takes control of program execution until the send-buffer is safe to be re-used again. What this means is that it’s safe to re-use the memory/variable you passed without affecting the data that is still being sent. If MPI didn’t have this concept of safety, then you could quite easily overwrite or destroy any data before it is transferred fully! This would lead to some very strange behaviour which would be hard to debug. The difference between the communication mode is when the buffer becomes safe to re-use. MPI won’t guess at which mode should be used. That is up to the programmer. Therefore each mode has an associated communication function:

| Mode | Blocking function |

|---|---|

| Synchronous | MPI_SSend() |

| Buffered | MPI_Bsend() |

| Ready | MPI_Rsend() |

| Standard | MPI_Send() |

In contrast to the four modes for sending data, receiving data only has one mode and therefore only a single function.

| Mode | MPI Function |

|---|---|

| Standard | MPI_Recv() |

Synchronous sends

In synchronous communication, control is returned when the receiving rank has received the data and sent back, or “posted”, confirmation that the data has been received. It’s like making a phone call. Data isn’t exchanged until you and the person have both picked up the phone, had your conversation and hung the phone up.

Synchronous communication is typically used when you need to guarantee synchronisation, such as in iterative methods or time dependent simulations where it is vital to ensure consistency. It’s also the easiest communication mode to develop and debug with because of its predictable behaviour.

Buffered sends

In a buffered send, the data is written to an internal buffer before it is sent and returns control back as soon as the

data is copied. This means MPI_Bsend() returns before the data has been received by the receiving rank, making this an

asynchronous type of communication as the sending rank can move onto its next task whilst the data is transmitted. This

is just like sending a letter or an e-mail to someone. You write your message, put it in an envelope and drop it off in

the postbox. You are blocked from doing other tasks whilst you write and send the letter, but as soon as it’s in the

postbox, you carry on with other tasks and don’t wait for the letter to be delivered!

Buffered sends are good for large messages and for improving the performance of your communication patterns by taking advantage of the asynchronous nature of the data transfer.

Ready sends

Ready sends are different to synchronous and buffered sends in that they need a rank to already be listening to receive a message, whereas the other two modes can send their data before a rank is ready. It’s a specialised type of communication used only when you can guarantee that a rank will be ready to receive data. If this is not the case, the outcome is undefined and will likely result in errors being introduced into your program. The main advantage of this mode is that you eliminate the overhead of having to check that the data is ready to be sent, and so is often used in performance critical situations.

You can imagine a ready send as like talking to someone in the same room, who you think is listening. If they are listening, then the data is transferred. If it turns out they’re absorbed in something else and not listening to you, then you may have to repeat yourself to make sure your transmit the information you wanted to!

Standard sends

The standard send mode is the most commonly used type of send, as it provides a balance between ease of use and performance. Under the hood, the standard send is either a buffered or a synchronous send, depending on the availability of system resources (e.g. the size of the internal buffer) and which mode MPI has determined to be the most efficient.

Which mode should I use?

Each communication mode has its own use cases where it excels. However, it is often easiest, at first, to use the standard send,

MPI_Send(), and optimise later. If the standard send doesn’t meet your requirements, or if you need more control over communication, then pick which communication mode suits your requirements best. You’ll probably need to experiment to find the best!

Communication mode summary

Mode Description Analogy MPI Function Synchronous Returns control to the program when the message has been sent and received successfully. Making a phone call MPI_Ssend()Buffered Returns control immediately after copying the message to a buffer, regardless of whether the receive has happened or not. Sending a letter or e-mail MPI_Bsend()Ready Returns control immediately, assuming the matching receive has already been posted. Can lead to errors if the receive is not ready. Talking to someone you think/hope is listening MPI_Rsend()Standard Returns control when it’s safe to reuse the send buffer. May or may not wait for the matching receive (synchronous mode), depending on MPI implementation and message size. Phone call or letter MPI_Send()

Blocking and non-blocking communication

In addition to the communication modes, communication is done in two ways: either by blocking execution until the communication is complete (like how a synchronous send blocks until an receive acknowledgment is sent back), or by returning immediately before any part of the communication has finished, with non-blocking communication. Just like with the different communication modes, MPI doesn’t decide if it should use blocking or non-blocking communication calls. That is, again, up to the programmer to decide. As we’ll see in later episodes, there are different functions for blocking and non-blocking communication.

A blocking synchronous send is one where the message has to be sent from rank A, received by B and an acknowledgment sent back to A before the communication is complete and the function returns. In the non-blocking version, the function returns immediately even before rank A has sent the message or rank B has received it. It is still synchronous, so rank B still has to tell A that it has received the data. But, all of this happens in the background so other work can continue in the foreground which data is transferred. It is then up to the programmer to check periodically if the communication is done – and to not modify/use the data/variable/memory before the communication has been completed.

Is

MPI_Bsend()non-blocking?The buffered communication mode is a type of asynchronous communication, because the function returns before the data has been received by another rank. But, it’s not a non-blocking call unless you use the non-blocking version

MPI_Ibsend()(more on this later). Even though the data transfer happens in the background, allocating and copying data to the send buffer happens in the foreground, blocking execution of our program. On the other hand,MPI_Ibsend()is “fully” asynchronous because even allocating and copying data to the send buffer happens in the background.

One downside to blocking communication is that if rank B is never listening for messages, rank A will become deadlocked. A deadlock happens when your program hangs indefinitely because the send (or receive) is unable to complete. Deadlocks occur for a countless number of reasons. For example, we may forget to write the corresponding receive function when sending data. Or a function may return earlier due to an error which isn’t handled properly, or a while condition may never be met creating an infinite loop. Ranks can also can silently, making communication with them impossible, but this doesn’t stop any attempts to send data to crashed rank.

Avoiding communication deadlocks

A common piece of advice in C is that when allocating memory using

malloc(), always write the accompanying call tofree()to help avoid memory leaks by forgetting to deallocate the memory later. You can apply the same mantra to communication in MPI. When you send data, always write the code to receive the data as you may forget to later and accidentally cause a deadlock.

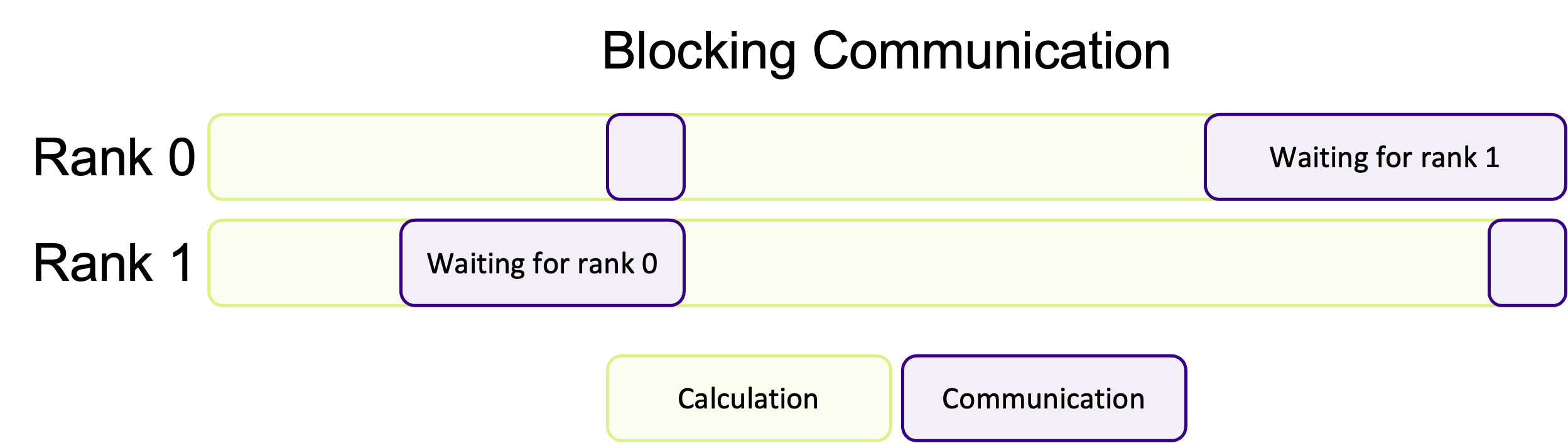

Blocking communication works best when the work is balanced across ranks, so that each rank has an equal amount of things to do. A common pattern in scientific computing is to split a calculation across a grid and then to share the results between all ranks before moving onto the next calculation. If the workload is well balanced, each rank will finish at roughly the same time and be ready to transfer data at the same time. But, as shown in the diagram below, if the workload is unbalanced, some ranks will finish their calculations earlier and begin to send their data to the other ranks before they are ready to receive data. This means some ranks will be sitting around doing nothing whilst they wait for the other ranks to become ready to receive data, wasting computation time.

If most of the ranks are waiting around, or one rank is very heavily loaded in comparison, this could massively impact the performance of your program. Instead of doing calculations, a rank will be waiting for other ranks to complete their work.

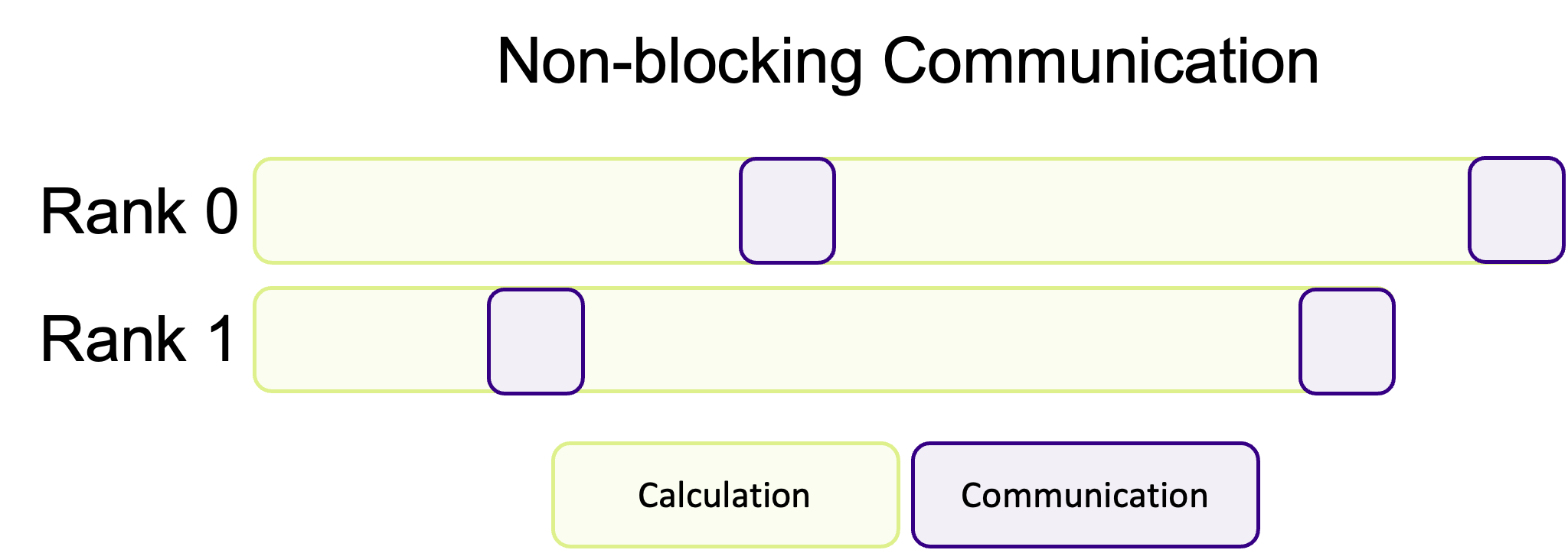

Non-blocking communication hands back control, immediately, before the communication has finished. Instead of your program being blocked by communication, ranks will immediately go back to the heavy work and instead periodically check if there is data to receive (which is up to the programmer) instead of waiting around. The advantage of this communication pattern is illustrated in the diagram below, where less time is spent communicating.

This is a common pattern where communication and calculations are interwoven with one another, decreasing the amount of “dead time” where ranks are waiting for other ranks to communicate data. Unfortunately, non-blocking communication is often more difficult to successfully implement and isn’t appropriate for every algorithm. In most cases, blocking communication is usually easier to implement and to conceptually understand, and is somewhat “safer” in the sense that the program cannot continue if data is missing. However, the potential performance improvements of overlapping communication and calculation is often worth the more difficult implementation and harder to read/more complex code.

Should I use blocking or non-blocking communication?

When you are first implementing communication into your program, it’s advisable to first use blocking synchronous sends to start with, as this is arguably the easiest to use pattern. Once you are happy that the correct data is being communicated successfully, but you are unhappy with performance, then it would be time to start experimenting with the different communication modes and blocking vs. non-blocking patterns to balance performance with ease of use and code readability and maintainability.

MPI communication in everyday life?

We communicate with people non-stop in everyday life, whether we want to or not! Think of some examples/analogies of blocking and non-blocking communication we use to talk to other people.

Solution

Probably the most common example of blocking communication in everyday life would be having a conversation or a phone call with someone. The conversation can’t happen and data can’t be communicated until the other person responds or picks up the phone. Until the other person responds, we are stuck waiting for the response.

Sending e-mails or letters in the post is a form of non-blocking communication we’re all familiar with. When we send an e-mail, or a letter, we don’t wait around to hear back for a response. We instead go back to our lives and start doing tasks instead. We can periodically check our e-mail for the response, and either keep doing other tasks or continue our previous task once we’ve received a response back from our e-mail.

Key Points

Data is sent between ranks using “messages”

Messages can either block the program or be sent/received asynchronously

Knowing the exact amount of data you are sending is required